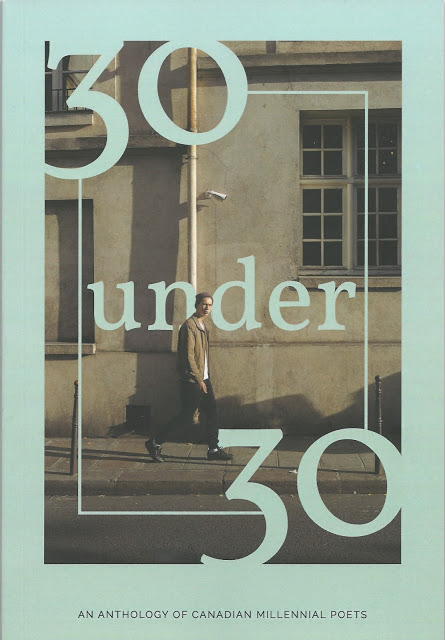

The word “millennial” doesn’t mean anything anymore. Although the new 30 Under 30 collection, published by In/Words Magazine and Press, describes itself as “an anthology of Canadian millennial poets,” it seems more interesting to me to think of it as a compilation of poems by digital natives living in cities all across Canada, whose birth years happen to range from 1987 to 1993. My goal with this essay isn’t to appraise each poem like a dog at a dog show or to question the editors’ decisions about which poets to include and which to leave out. Rather than write a review, I want to look at this anthology as a whole and simply highlight common threads, stylistic quirks, and shared concerns.

Since I am writing this for the Montreal Review of Books, I’ll focus primarily on the five authors in the anthology who currently live in Montreal, all of whom I know or have met, though who knows if they’ll all still live here by the time this essay is published. Montreal’s Anglophone literary community, of which I am part, rarely stands still for very long: new writers move here for school or seeking a new life, others move away because they can’t find a proper job or because they feel they’ve exhausted the city. Still, even if they decide to move away, Montreal’s lively spirit and DIY attitude is likely to permanently influence these writers’ works.

While the 30 Under 30 anthology frequently discusses the living nightmare that is dating and navigating personal relationships (from Cassidy McFadzean’s poem: “If all my father figures are trying to fuck me, do I still have daddy issues?” and from A. Zachary’s piece: “thank you for continuing to be attracted to me when my stomach isn’t flat”), Montreal-based poet Ashley Opheim’s poem, “Plastic Watermelon,” goes in a different direction, choosing instead to focus on two people sharing a moment of pure bliss. My favourite aspect of this piece is the way it constantly plays with scale: lovers hold one another in “the tiny rain,” flowers are compared to spaceships, and the “space between mountains” is made the same size as the space between two breaths. “I am gigantic for you,” Opheim writes. “I am a tiny spaceship.” If anything, I am tempted to compare this piece not to another poem, but to Everything, a recently released video game by artist David O’Reilly that also makes the small seem big and infinite and the large feel tiny and manageable. While the moments depicted in this poem may end up being just a few fleeting hours of happiness, Opheim expands them into an eternity.

Scale is also apparent in a poem by Montreal’s Jessica Bebenek, in which iron beams are “matchsticks” and a kiss is described as the “whole city rushing suddenly into a single sensation.” It appears as well in Vancouverite Kayla Czaga’s piece, in which the Milky Way becomes an ultrasound. This repeated pattern of playing with scale made me wonder if it was a by-product of poets living in large, sprawling cities and being constantly surrounded by tall buildings and skyscrapers. Compared to Opheim’s piece, Bebenek’s vision of romance comes across as more level-headed and practical, a kind of self-preservation tactic that seeks to anticipate and prevent future disappointment. “You kiss with acceptable pacing,” she writes. “How wholly unremarkable to be in each others’ lives.” This cautious approach to love is probably not surprising and permeates other poems in this collection (Ben Ladouceur: “Some of us will remain unwed”; Dominique Bernier-Cormier: “Love switches on and off for no reason like a haunted television set”; Emily Chou: “I unstitch myself for you but I will not wear these clothes again and you cannot have me”).

Also common in this collection is anxiety about performance and performing, about vanity and physical beauty, about watching and being watched, even when you’re entirely alone. Montreal’s Klara du Plessis writes, “I struggle to understand those who spend 45 minutes attending to their face, when I stare at myself for hours it’s a subtraction of self, not an add-on,” which I am tempted to connect to a line in Julie Mannell’s piece, “A Poem Against Pretty Bodies,” in which she says, of cutting, that, “I do it like a little girl. I do it the wrong way on purpose.” This constant mental pressure to perform, to be simultaneously a passive audience and an active performer for others, is probably best summed up by a line in joseph ianni’s piece: “Dear body, I want to take the beating for you.”

While these poems, in true Canadian fashion, frequently anchor themselves in the natural world by referencing Canadian locations (Turtle Lake, Happy Valley, Nemeiben Road), water or the ocean (Selina Boan describes “watching water hesitate”), or astronomical objects (Jessie Jones: “to bleed in regular intervals with the moon”), they also let the noise of the internet and global capitalism in. Cassidy McFadzean notes that “The moment I’ve met each #squadgoal my mind turns to self-destruction” while Trevor Abes repurposes the language of shitty consumer plans when he describes a relationship as a “no-commitment free trial.” In his piece, which is centered around The Veiled Virgin, a meticulously crafted marble bust of the Virgin Mary displayed in Newfoundland, Montreal’s Patrick O’Reilly uses a carefully placed “ye” to give his poem a local flavour and a sense of place, which feels like a similar strategy to McFadzean’s #hashtag: it’s a way to let the outside world in. It’s also interesting to compare O’Reilly’s mention of God (“Cliché won’t revive what’s gone to stone, God knows”) with Ottawa’s Ian Martin (“god loves me so god is gay but if he loves you then he’s straight but if god is not a he or a she then we’re all gay”). If O’Reilly’s “God” exists in the context of religious institutions and traditional faith, Martin’s “God” feels more like a kind of LOL God that lives on Tumblr and reads queer and gender theory.

Montrealer Jay Ritchie’s poem, “Multi-Level Marketing,” is probably the purest example in this collection of letting the noise in. His poem frequently stops to copy-paste faux-profound aphorisms before undermining the quotation by adding, “I read that on Tumblr” or describing it as “advice from the Lululemon bag.” The poem’s style nails perfectly (at least for me) the feeling of going for a walk and losing myself in thoughts, thinking about my problems, random memories and one-liners I’ve read online while being surrounded by language imposed on me by corporations. For this reason, the most poignant parts of Ritchie’s poem, I feel, are the ones that repurpose capitalism to create beauty, such as when he describes himself as “exceeding everyone’s expectations like water in a Coca-Cola bottle” or when he simply remarks, “I buy plastic to feel normal.”

While I could use the points above to try and make some sort of grand argument about the next generation of Canadian poets, in the end, maybe the best thing I can say about In/Words’ 30 Under 30 Anthology is that reading it gave me hope. I like how these pieces seem interested in pure communication and self-expression rather than getting bogged down by tradition or format, almost like they’re collectively trying to imagine a new path forward for Canadian poetry. To quote Jay Ritchie’s piece, with these poems, “I can imagine a better world.” mRb

0 Comments