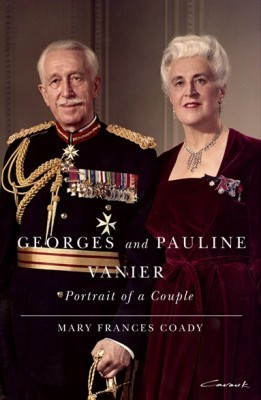

Georges and Pauline Vanier

Portrait of a Couple

Mary Frances Coady

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$34.95

Paper

296pp

Uncorrected proofs

978-0-7735-3883-2

The original power couple, Georges and Pauline Vanier partook in – or were close observers of – many of the great events of the early twentieth century. “I ask only to serve,” was their personal as well as public maxim.

Born to a Francophone father and Irish mother in Montreal, George (he was to Gallicize his name later, adding the “s”) Vanier was studious and serious. Not long out of law school, he joined the Canadian army at the outbreak of World War I and was instrumental in founding Canada’s first French Canadian battalion – the famed 22nd Regiment, better known as the Van Doos.

This war experience, including the loss of a leg, served Vanier well his entire life, helping to forge his not-exaggerated reputation as stalwart, intelligent, and courageous. Appointed to a series of increasingly distinguished positions – aide-de-camp to Governor General Lord Byng; member of the Canadian military delegation to the League of Nations; secretary to the High Commission in London; Envoy Extraordinaire to France – Vanier’s rise through the ranks of Canadian diplomacy was never without merit.

Nor was it ever without Pauline. A woman of little formal education, Pauline Vanier (née Archer) was unani- mously regarded as critical to her husband’s success. A relationship founded in their shared spirituality and dedication, it was also, over time, a very real partnership: “We work as a team,” Vanier reiterated to External Affairs at the end of World War II. For his part, Lester B. Pearson, then ambassador to Washington, communicated to Georges the high praises “which I hear about you and your mission, and, more particularly, about your wife.”

Through early hardships, frequent trans-Atlantic moves, tumultuous events, and five children, the Vaniers forged a complimentary relationship out of radically different temperaments. Drawing from their diaries and copious letters to each other, Coady has ready access to very personal struggles, fears, and ambitions. The author’s real strength, however, is in perceiving how these struggles intersect and reflect the world around them. From the distinct differences in their Catholic faiths, to the battlefields of World War I, to the fall of France to Nazi occupation, to the post-war years of shuttle diplomacy, to Vanier’s appointment as Canada’s first French Canadian Governor General, Georges and Pauline Vanier is also a compelling history of the first half of the twentieth century.

Along with the Vaniers, secondary characters come vividly to life. Julian Byng, the British diplomat who led the Canadian charge at Vimy but who is best remembered for the “King-Byng Affair,” is jovial, opinionated, and loyal. Loathing “pomp and ceremony and pretension,” he remains the cou- ple’s closest friend until his death.

Charles de Gaulle, on the other hand, in spite of the fact that Vanier was the only foreign diplomat during World War II to recognize (and lobby for) de Gaulle’s leadership and the role of the French resistance, consistently repaid the debt in diplomatic snubs. This culminated in 1967, when he sent a low-level minister to Vanier’s funeral. Three months later he managed to express a national rift for generations to come with his “Vive le Québec libre!” from the balcony of Montreal’s city hall.

In refreshingly clear prose built upon tremendous research, Coady has written the story of a couple who served Canada not only in their lifetime, but through future generations. To wit, the Vanier Institute of the Family as well as the humanitarian work of their children: Jean Vanier (l’Arche), daughter Thérèse (pioneering female physician), Georges (Trappist monk at Oka).

It’s tempting to assume that a very modern and preoccupied Canada has lost that mid-century sense of service and public good. But the words of Jack Layton, as relayed by Reverend Hawkes, cannot help but sound slightly familiar: “How I live my life every day is an act of worship.” Georges Vanier couldn’t have said it any better. mRb

0 Comments