If you’re trying to reach Josh Freed, don’t call him on a Friday afternoon. When most of us are wrapping up our workweek, he is fiddling with his humour column, trying to smooth out the kinks so that it is ready to go to press in the next morning’s Montreal Gazette. His column has been appearing on Saturdays for over twenty years now – long enough to make us wonder how he still has anything to be funny about. But “our speed-crazed, tech-obsessed, password-plagued, financially- jittery, fitness-fetishist, gluten-sensitive, fatness-fearing world” is absurd enough to keep him laughing, and to keep us laughing with him.

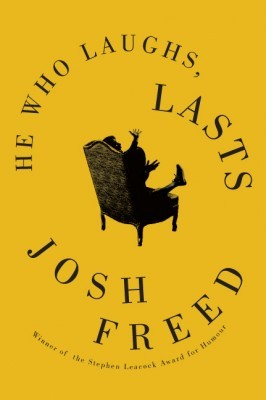

His jokes just became more permanent in his new collection of columns, He Who Laughs, Lasts. These pieces, selected from the last twelve years of his Gazette column, touch on everything from politics to parkas, iPhones to Anglophones.

The book isn’t the only excitement Freed has seen this year. In March, he added a column in L’actualité to his usual work as an English journalist and documentary filmmaker. The first piece he wrote, “Bonjour, mon nom est Josh Freed,” became the most clicked article ever published in L’actualité.

He Who Laughs, Lasts

Josh Freed

Véhicule Press

$20.00

paper

156pp

978-1-55065-346-5

Eric Boodman: You have been sitting on these columns for over a decade. What made you want to put out a collection now?

Josh Freed: It was a good year for Montreal. First you had the student strike that went on and on, then you had the crazy tense PQ election, then you had the never- ending Charbonneau scandal, then you had the mayor’s resignation. All that was missing was an earthquake, except we had one of those too. The whole city was on this never-ending roller coaster, and I thought that the only way to enjoy the ride was to laugh. The higher the tension level, the more people laugh. And now is the discontent of our winter, so it’s a natural time to do it. A good smile is as good as a good parka for the average Canadian.

EB: What is the column-writing process like?

JF: Being a columnist makes you concentrate on the world: everything is a potential column. But by nature I’m a deadline writer. Friday is a religious day for me: I’m not allowed to do anything else; it’s humorous Sabbath. My IQ rises about fifty per cent in the last two hours of writing. Terror breeds comedy, you know? When I’m really, really up against the wall, I become funnier, I write better.

EB: You are now writing columns for L’actualité in French. Can you talk about your upbringing and the kind of French education you had?

JF: I’m a classic Montreal Anglo: I’m Jewish. English Jews were sent to the English Protestant School Board. So I spent all my time learning all these Protestant hymns that only Jews in Montreal can sing. I could go to any synagogue in Montreal and lead them in “Onward Christian Soldiers.” While they were teaching me all these songs, they weren’t teaching me French. My French teacher was Mrs. Schwartz. She had an accent that was one part Paris, two parts Cavendish Mall. I couldn’t go east of Schwartz’s Deli and be understood because my accent was so terrible. Back then, it was terra incognita. Today, young Anglos like my son go to French school. He’s got the French accent of a lumberjack and the wine sophistication of a sommelier.

EB: Were you the class clown in school?

JF: No, I was the class writer. I’ve learned to be funny on stage in recent years – I spent six months of my life practicing for a comedy show at the Centaur – and I do a lot of public speaking, so I’m okay. But I’m not a joke teller. I don’t know any jokes. I don’t remember jokes. I don’t laugh at jokes; I don’t even like jokes. I like observational humour, thoughts on life, wordplay. I don’t like the three-part joke. A man walks into a bar with a parrot on his shoulder, I fall asleep. One of the great burdens of being a humour writer – the only burden – is that everybody wants to tell me jokes.

EB: Is having Stephen Harper at 24 Sussex good for Canadian humour?

JF: Yeah, he’s a great source of humour: he’s so serious you cannot not write humorously about him. He’s like a robot designed in some secret laboratory in Alberta. The man who shakes hands with his children. His bizarre adoration for the monarchy. He doesn’t seem to believe in parliament. But doing humour about Harper in Quebec is effortless because no one in Quebec can stand Harper.

EB: What do you, as a columnist, think of the “newspaper crisis” that everyone says is at hand?

JF: There’s no doubt newspapers are in a crisis. When I hand my seventeen-year-old son the newspaper, I might as well be handing him a tree trunk: that’s how foreign it feels in his hands. And my wife’s a journalist and I’m a journalist. Our house is twenty-five per cent furniture, thirty-five per cent newspapers. Despite that, my son grapples with newspapers. Everybody’s switching over to the Web. They think they can get their information online. The thing they don’t realize is that almost all the news online comes from somebody’s newspaper somewhere. You have to have somebody out there with reporters who cover the news. Newspapers and a couple of TV stations have reporters, but most radio stations get their news from newspapers, and most TV news stations get their stories by following newspapers. And all these little online sites steal newspaper stuff and recirculate it. So you kill the newspapers, you kill the news.

EB: You seem to find a lot of inspiration in technology. Can you talk about that?

JF: I write a lot about technology because it’s the centre of our existence. If Descartes had been alive today, he would’ve said “iPhone therefore I am.” It’s an app-happy society. If your pollution-measuring app is working you’re happy that day, if you can’t download it you’re sad. Who could imagine these would be the great problems of an age? Everyone’s got password amnesia. One of them is based on my grandmother’s maiden name backwards followed by the year I took oboe lessons. The average person has more passwords than the chief of command in World War II. Why do we need all this security? Are burglars going to break into my house to rob me of my messages? They can steal my messages, as long as they answer them!

EB: Do you think there’s something fundamentally depressing about these absurd obsessions?

JF: No. We live in an incredibly luxurious age in the Western World. We don’t worry about the things other humans have worried about throughout our existence: starvation, tuberculosis, diphtheria, the black plague, infant mortality. We have the luxury to sit around and obsess about all these tiny terrors like cellphone rays, humidifiers that kill, or sick car syndrome. People throughout history would have torn out their fingernails to worry about the things we worry about. mRb

0 Comments