Guy Delisle made his name by spinning a modern variation on the theme of the innocent abroad. Making the most of his role as a househusband accompanying his NGO-employed wife on extended international assignments, the Quebec-born, France-based cartoonist and filmmaker took notes and made sketches about his experience getting to grips – or failing to, as the case may have been – with a series of foreign places and cultures. The result was a string of books – Shenzhen: A Travelogue from China, Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea, Burma Chronicles, Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City – that attracted a large and devoted following.

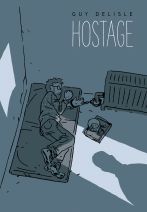

Having shown, using first-hand experience, how a visitor’s best intentions can go awry, Delisle now tells someone else’s story of the same scenario taken to an alarming extreme. Hostage is the account, as told to Delisle, of how a Doctors Without Borders worker in Nazran, Russia, was kidnapped by Chechen rebels in 1997 and held for three months in an undisclosed location. And there, handcuffed to a radiator in a bare room with a boarded-up window, trying to maintain hope, is where we find Christophe André for most of this remarkable book’s 400-plus pages.

Hostage

Guy Delisle

Translated by Helge Dascher

Drawn & Quarterly

$32.95

cloth

436pp

9781770462793

The solutions, for Delisle, are both visual and textual. Hostage employs a very different look from the one Delisle’s readers have come to expect. Realistically rendered settings populated by highly stylized human figures were the norm, but now the contrast has been smoothed out and the people made less cartoonish, which is fitting for a story with very little scope for the comical.

For whole pages at a stretch panels are rendered in tones so dark you have to strain to see the images within them, but that is the point: André had to strain, too. At times we see literally what he saw: the corner of a ceiling at an askew angle, a bare, dangling light bulb, nothing at all. He’s in a vulnerable state where almost anything can take on the darkest implications, or be spun into cause for desperate hope. One of his captors appears in the doorway holding a small knife, but he may just have been absentmindedly holding the same innocuous implement he had just used to butter his toast. And so it continues, with no end in sight.

Big as this fifteen-years-in-the-making book is, its relative paucity of text means that it can be worked through fairly quickly. But readers are best advised to take it slow. Linger over it, contemplate these images, even if many of them might appear nearly identical to the ones that precede and follow.

For a true story with historical and geopolitical ramifications, Hostage is light on context, and some Chester Brown-style endnotes beyond the bare-bones epilogue might have been useful in filling out the picture. The Chechens in the story remain ciphers, and many questions are left dangling. What is the role of the seldom-glimpsed woman in the house where André is being held? How would a child at home feel about stumbling onto the knowledge that a man is handcuffed in a room down the hall?

We never do find out, and are left to work out the story’s political implications for ourselves. But to ask for the answers is, in effect, to ask for a different book. Delisle has set himself a strict set of parameters, and, within his remit, he succeeds completely. More than telling a gripping story, Hostage opens up whole new possibilities for where Delisle might go next. mRb

0 Comments