I Am a Japanese Writer is Haitian-born author Dany Laferrière’s thirteenth novel, newly translated from the original French. Douglas & McIntyre is publishing the book this fall alongside a reissue of the author’s first novel, 1985’s How To Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired. As part of a campaign to introduce the prolific francophone author to English-Canadian audiences, these two novels separated by twenty-three years share the distinction of being among the most provocatively titled in his catalogue.

The author must be aware of this fact, as I Am a Japanese Writer is essentially about an unnamed Black author who one day announces, without much foresight, that he will write a book by that very name. The contents and message of the book are beside the point; the title itself piques interest. Everyone from the author’s publisher to his fishmonger latches onto the boldness of a statement that, in an ethnically defined world, will no doubt draw controversy and inspire debate.

Of course, there is one small problem in all this: our nameless author has no ambition to write such a novel, nor does he even desire to learn more about Japanese culture than the little he already knows. And so the bulk of the novel involves the author avoiding everything to do with the novel he is supposed to write, as he wanders among an improbable cast of Montreal characters, all of whom are as hastily drawn as the novel’s driving premise.

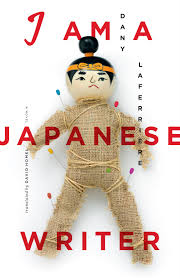

I Am A Japanese Writer

Dany Laferrière

Translated by David Homel

Douglas & McIntyre

$22.95

hardcover

182pp

978-1-55365-583-1

Though Laferrière’s literary tastes range widely, in I Am a Japanese Writer these influences are often employed in a watered-down form that forsakes depth for brevity, complicating his ideas about culture and identity and ultimately blurring the novel’s ambitions. Laferrière’s style is as peculiar as the author he portrays, whose strident sense of minimalism can sometimes verge on simple laziness. He invests little effort in plotting, context, meaningful interaction, or characterization – the meat that could have benefited this skeletal novel of ideas – instead opting for a narrator who operates at a conspicuous distance from the world and people around him.

And what of those ideas? In I Am a Japanese Writer, Laferrière may very well want to provoke a transcendence of much-trodden ethnic stereotypes and the boundaries they create. He seems to be saying that these stereotypes invade all our dealings with society, and that a Black man claiming to be a Japanese writer would create an uproar in the preconceived order of ethnic ideals. Yet Laferrière never attempts to raise his characters above these misconceptions. Koreans are easily confused with Japanese, the Japanese are consistently condescended to, the Greeks are snide and mean, and Blacks are the misunderstood victims of their perceived sexual potency and rage. It’s all delivered in a manner that’s too tame to be offensive, and too familiar to be eye-opening. Is Laferrière really saying anything at all about our cultural dependence on ethnic tropes, or is he simply moving around preexistingpieces for a few laughs?

One can argue that this is the basis of satire, to reflect and make light of our world’s limitations, and that the novel’s metafictional elements resolve the many other questions left unanswered. But given the fact that these are questions that warrant probing, and which Laferrière seems eager to raise, that seems too easy an excuse. mRb

0 Comments