Candy production dropped. Butter was hard to get. Women joined the workforce. And tens of thousands of men were in uniform and far away from home.

World War II didn’t leave Montreal a flattened ruin, as it left so many cities overseas, but it did affect every aspect of life in the city; some things temporarily, others permanently – none more so than the legions of sons and husbands who never came home.

It’s an interesting area of inquiry – changes brought about by war in a metropolis well removed from the war itself – and it’s one handled very nicely by author Patricia Burns in Life on the Home Front, a thorough, well- organized, and very readable history of Montreal in the 1940s. It isn’t a scholarly work, and some readers will find fault with the absence of footnotes and detailed sources. But there is a lot of information here, and it is well assembled, well presented, despite some misspelled words – it’s the Capitol Theatre, not the Capital, and it’s Delorimier Stadium, not Delormier – and inconsistent punctuation.

Life on the Home Front – which follows Burns’ earlier histories, They Were So Young: Montrealers Remember World War II (2002) and The Shamrock and the Shield: An Oral History of the Irish in Montreal (2005) – begins with a survey of the city just before the war: the era of King, Duplessis, and Houde; of linguistic division and economic hardship; of the “Canadian führer” Adrian Arcand; and of the Empire-rallying royal visit of 1939. English Montrealers generally supported the war, French Montrealers didn’t. But both sides joined up in substantial numbers, some out of a sense of duty or a sense of adventure, others for family tradition. Many just needed a job.

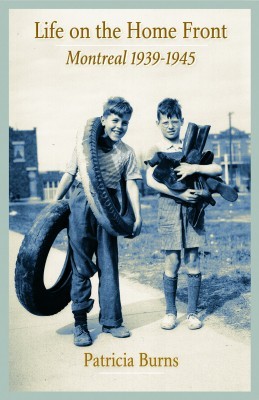

Life on the Home Front

Montreal 1939-1945

Patricia Burns

Véhicule Press

$20.00

paper

292pp

978-1-55065-341-0

The fear of losing loved ones was a constant for the folks at home, and the appearance of a telegraph boy dreaded. Burns speaks of a mother standing at the stove and knowing, suddenly, unmistakably, that her son was dead.

The telegram came several days later. There were 1.1 million Canadians in uniform in World War II (out of a population of 11.5 million). Two-thirds of them were under 21. And 50,000 of them were women. For many more women, though, the war meant work outside the home for the first time, and a new sense of independence. The Catholic Church in Quebec disapproved of the trend, but magazines were generous with advice to women on how to maintain their “femininity” while doing the work of three men.

Montreal factories turned out thousands of planes, tanks, weapons, and explosives during the war, much of it destined for British and Russian armies. The emphasis on armaments meant fewer domestic goods, automobiles, new homes, and foodstuffs. Here it was the federal government that stepped up with timely advice, including a suggestion to “serve meat gravy on potatoes instead of butter.”

Montreal had always enjoyed a lively entertainment scene, and during the war, with thousands of soldiers and sailors passing through, the city’s restaurants, nightclubs, and brothels were busier than ever. Celebrities regularly came through town, many pitching Victory Bonds, and Charles de Gaulle, the Free French leader, visited in 1944 to stir up enthusiasm for the cause. “Vive le Canada,” he cried from a Windsor Hotel balcony, a sentiment he appears to have forgotten when he returned 23 years later and cried “Vive le Québec libre” from a balcony on city hall.

The end of the war, in Europe in May 1945 and in Japan in August, brought huge, happy crowds into the streets of downtown Montreal. Car horns, ships’ whistles, and church bells provided a background din. It was a war, as Burns says, “that, in its scope, cruelty and depravity was unprecedented in the blood-soaked annals of the world.” Yet it left Canada an industrialized, successful, wealthy, and much- admired place, a legacy from which we still benefit. mRb

0 Comments