A question from a friend was the catalyst for Museum of Kindness, Susan Elmslie’s latest book of poems. “She asked me, ‘What’s your genre?’” the poet recounts, “And she meant, essentially, what metaphor speaks to where you are in your life right now?”

With Museum of Kindness, her second poetry collection, Elmslie responds to that question and explores how we find the metaphors we need to make sense of lived experience. In a generous, extended email correspondence, Elmslie told me about her approach and expanded on her notion of “genre.”

“How does a genre become a genre?” she wonders. “How do the contours of the thing, the experience that we confront, take shape, until the phenomenon can be recognized and named in a word or phrase that encapsulates its gestures and conventions? Holocaust. Active Shooter. Fetal Abduction. These terms came after the phenomena.”

Many of Elmslie’s poems chart the course from raw experience to more serene understanding, even epiphany. “At least you got a poem out of it,” quips the speaker of “Material,” suggesting the fraught relationship between the moments we live and the stories we tell about them. A poem is “one of the perks of pain,” the only consolation for the “endless supply of material” life unfailingly supplies.

Much of the material from which Elmslie draws is personal, although she, like many poets who write in a similar vein, puts quotes around the descriptor “confessional.” “Poetry’s still artifice, even if it does intersect with lived experience in significant ways.”

To call these poems “confessional” is to say that they mine the poet’s interior, but it is not to say only that. As poet Rachel Zucker has said, “surgery is not an act of intimacy.” A poem is not made by self-exposure alone. Rather, these poems explore and sometimes undermine the boundaries of the self, scraping down private experience until something more human (perhaps “generic”) than individual is revealed.

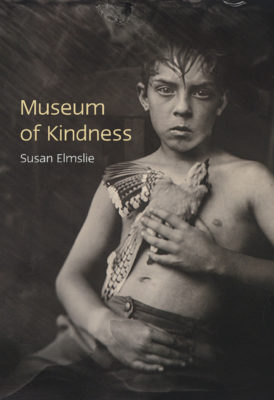

Museum of Kindness

Susan Elmslie

Brick Books

$20.00

paper

113pp

9781771314671

I can tell you there is a static silence

between reports of a gun; bulletspierce drywall; we were too afraid to move

a filing cabinet to block the door;when the smooth-jawed SWAT officer

ordered me to hold it open for my studentsthen swung around to cover my back I felt

his core hot and trembling through Kevlar.

The poem feels utterly controlled and unflinching, even as trauma radiates heat from underneath. It is a recollection broken into short breaths, the reality of the experience accumulating, snowflakes into snow, as images land one by one. Elmslie often operates this way: a careful accounting of images, sensations, and ordinary moments that coalesce into a sum more meaningful than its parts. The effect can be satisfyingly surprising, but it is a premeditated kind of surprise, like someone appearing in a doorway before you hear their footsteps.

“I can spend years on revisions, approaching the poem totally coldly,” Elmslie reflects. “And then suddenly click or sproing. I feel a sense of ‘yes, that’s it,’ when a poem coalesces and there’s a match between what gets down on the page and what I didn’t know I knew about my subject or experience … As Frost said, ‘No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.’”

The aim of reworking poems over such a long period – Museum of Kindness “came together over eleven years,” Elmslie says – is to depersonalize the material and evaluate it more dispassionately. Interestingly, the poems often embody such shifts our perception takes over time. The section related to the Dawson shooting closes with “The Worst,” which asks, “How do we get a handle on the worst / when it’s a moving target”? The horror of the incident diminishes in retrospect as it is assimilated into the larger, ordered arc of a life, into which other traumas present themselves for comparison.

The subsequent section of poems, entitled “Threshold,” follows a similar narrative arc from chaos to order. Beginning with a difficult pregnancy and birth, the poems trace a child’s diagnosis (“My baby’s perfect but his brain won’t let him talk,” moans the voice of “Broken Baby Blues”) and his parents’ struggle to find footing on the steep slope of their new reality. Here, too, Elmslie draws from personal experience, that of parenting two small children, the younger of whom has autism. These poems walk a more delicate line of self-exposure. While the “gestures and conventions” of a school shooting are familiar to most of North America by now, these poems describe a more obscure “genre,” the experience of loving and caring for a child with a disability: the initial, disorienting grief; the grinding exhaustion; the scrutiny of doctors and well-meaning strangers; the harrowing uncertainty about the future. From “Going Under”:

Infant, from the Latin for unable to speak.

At five and nonverbal, our boy’s still golden.

People like to say, No one ever goes to college in diapers.

These poems feel resolutely truthful, yet appropriately protective. Elmslie never lets it all hang out; she is aware of the stakes of revelation.

“These poems, to some degree, put me out in the world as a mother of a child who is differently abled, who is different,” she acknowledges with a tinge of dread. “Some people may be curious. Some people will turn away. And some people will see their own experiences reflected. I expect that there will be judgement. There may also be connection, an opening.”

The “confessional” core of the book is bookended by poems that explore less loaded themes, giving the collection an arc of its own, a course plotted into darkness, but then methodically back out again. Many individual poems chart similar journeys, the slow progress of hindsight, the process by which we order our moments to create meaning. Trauma is metabolized here rather than raw. An initial sense of having driven off the map evolves into acceptance and intuitive knowledge of new terrain.

“It takes me time to process experiences,” the poet replies when asked about the difficulty of airing personal pain in her work. “With appointments and daily encounters, the words are sometimes painfully superficial and perfunctory. Speaking from a place of exposure lets me go deeper, to where we feel the impact of those exchanges, to where we are changed by them.”

Elmslie’s work suggests that this is poetry’s function: to give shape to those human experiences that lay outside of language. The act of naming the unnameable is a consolation for facing the terrifying unknown. Poetry, as her poem of that name contends, contains both “lashing / and balm.” mRb

0 Comments