In Endre Farkas’s novel Never, Again, the protagonist Tomi, a young Hungarian Jewish boy, tries to digest the history that has abruptly been unveiled to him: “He wants to ask his parents so many questions. He wants to know the meaning of big words like de-se-cra-tion. He wants to know what a ghetto is, and what people concentrated on while they were in a concentration camp. But something tells him he isn’t supposed to be asking these questions now. Maybe that’s what it means to be a grown-up … knowing when to ask questions and when not to.” This reflection captures the heart of the novel’s central themes: When, and with whom, should knowledge of atrocities be shared? Is it always better to possess such knowledge; and is the idea that knowledge of history will keep us safe merely an illusion?

The novel is set during the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. The uprising began as a student revolt against the Soviet-controlled government that had been established at the end of World War II, and quickly escalated into nationwide violence. The conflict led to significant loss of life, as well as many Hungarians fleeing as refugees. Of those refugees, an important percentage were Jewish; many of these individuals were alarmed at how the unrest of the uprising emboldened anti-Semitic sentiment, and feared the possibility of a return to Nazi-era politics.

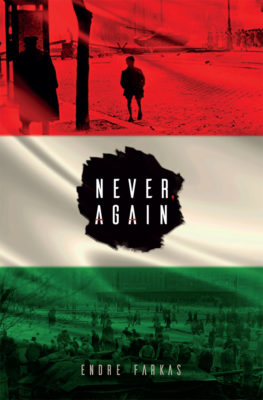

Never, Again

Endre Farkas

Signature Editions

$19.95

paper

216pp

9781927426869

The figure of a child protagonist not yet fettered by the burdens of history lends the novel its greatest strength: a subtle balance between everyday ubiquity and unimaginable horror. Sparse, straightforward prose effortlessly captures the voice of a young boy but can also be redolent with details when it switches into the perspective of the parents. Scents and tastes play a particularly prominent role, such as when Sanyi recalls the first time he met his wife: “He inhaled the lavender fragrance of her hair and the fat flavoured steam of chicken soup, the sweetness of boiled carrots, and the meat-rich sholent. He fell in love.” This emphasis on capturing sensory impressions, as well as the sincerity and simplicity of Tomi’s emotional reactions to moments like receiving hockey jerseys from his aunt in Canada, imbue the novel with a nostalgic fragility. Even while Tomi remains ignorant of both the horrors that have come before him and those that lie ahead, the reader cannot help but see the events of the plot unfolding through a lens of historical knowledge.

The certainty of Tomi’s eventual loss of innocence haunts the novel, as does an even darker sense of cyclical repetition. The strategic punctuation of the title raises the spectre of inevitability. Farkas leaves readers both with the implication that knowledge alone will not guarantee a better future and a lingering unease about what, if any, recourse can ensure that historical catastrophes are not allowed to reoccur.

0 Comments