“First thought, best thought.” Allen Ginsberg coined the phrase. Probably influenced by his studies in Buddhism, he was essentially saying that the best way for an artist to get at the truth is by not letting the left side of the brain trip up the right. Just get it down. Don’t overthink. There can be few better demonstrations of the adage in action than Pascal Girard’s Nicolas.

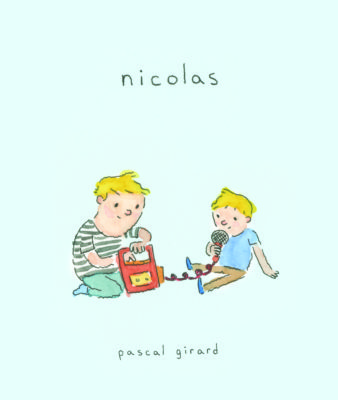

First published in 2008, the small, sparsely rendered story of a nine-year-old boy’s attempts to come to terms with the death of his five-year-old brother did more than just launch the comics career of Jonquière-born Girard; it became a word-of-mouth cult item inspiring a rare devotion in its readers. People press Nicolas on friends, give it as a gift, revisit it in times of need.

Grief is one of the hardes subjects to render convincingly: err on one side and you’re left with little more than despair, err on the other and you can easily tip over into the maudlin. A big part of Nicolas’s power lies in its uncanny evoking of a young boy’s emotional landscape and thought processes. Girard avoids the common trap of imposing an adult sensibility onto a child: his nine-year-old self, as portrayed in the book, is as bewildered by the world as any of his contemporaries, a feeling compounded by his dealing with an unimaginably huge trauma in a setting where those best equipped to help him appear determined to keep him in the dark.

Nicolas

Pascal Girard

Translated by Helge Dascher

Drawn & Quarterly

$16.95

cloth

112pp

9781770462625

Happily, the original is not tinkered with, and the new story doesn’t try to ape the visual signature or naive voice that made the book unique in the first place. We’re not allowed to forget that, not only has the central character aged from childhood to adulthood, but the artist is also ten years down the line artistically from where he was: his line and composition have evolved, his sense of how much to put in has expanded but remained powerfully economical. You can still “read” Nicolas in roughly fifteen minutes. But you’ll probably find you can contemplate it for years.

“I said, ‘I’m going to try to do a story – not a book – in a weekend,’” Girard tells me over the phone from his home in Mile End, remembering the low-key origins of Nicolas. “It was just an exercise for myself. I wanted a subject that I already knew.”

Such an unassuming and private origin story chimes nicely with the way Girard first discovered his talent – on his own, in the Saguenay community where he grew up.

“It’s funny, my girlfriend is from Saskatoon and she always says I grew up in a small town,” he says. “But if you add up the population of the surrounding communities, Jonquière is about the same size. I have memories of it, but I don’t have too much attachment. I was in school, drawing at night, playing in the fields and woods. Most people enjoyed hockey. I didn’t. Mostly, my head was in comics, and in movies like Ghostbusters.”

In the nature-versus-nurture debate, Girard’s experience would seem to represent a firm case for the former. “My father worked for the city,” he recalls. “He was also a hunter and fisherman, and I guess I never really cared for those things. My mother worked for Alcan, the big employer there, as a computer programmer. There were no books and no music in the house, and that’s interesting, because my brother Joël eventually did a master’s in classical music. So I don’t really know how people pick up on these things.”

Girard was drawing from as early as he can remember, though he makes no great claims for his first efforts. “I was mostly doing it for myself. I didn’t really show it to anybody, though my mother was aware of it and encouraged me. A lot of it was just copying comics, mostly action comics like Batman. In one of them, Asterix was in Lac-Saint-Jean because he needed blueberries. I did that kind of thing until I was twelve or thirteen, and then I pretty much stopped drawing for ten years.”

When the creative bug came back it was more or less at random, in Chicoutimi, where Girard had gone to study film.

“There was a little bookstore, no longer there, and I discovered some books by Jimmy Beaulieu, an artist who’s maybe not that known to English readers but is well known in the Quebec comics scene. He eventually became my first publisher.” The epiphany moment came when Girard first met Beaulieu at a book fair. “He was drawing on cheap paper with a cheap pen, the cheapest Bic you could buy. That opened something up for me. You don’t need a big drawing table, you don’t need anything fancy. I had never pictured the process could be that direct.”

As already implied, deciding to do a story about the loss of his brother wasn’t as emotionally complicated for Girard as might be assumed. To hear him tell it, practicality was the deciding factor. “It’s funny, sometimes you’re in a better spot than at other times with grieving, and I was at a good place in my life, so the choice of subject was actually pretty easy,” he says. “I had many years’ worth of little stories already, so I made a list of things I could tell, started drawing, and at the end of the weekend it was done.”

Once it was on paper, Girard says, “I thought, ‘Well, this is raw, but maybe I could show it to somebody.’ So I showed it to my girlfriend at the time. I don’t remember if she liked it. When it was published and started having success, I thought, ‘This is happening too fast. I’ve only just started with comics.’”

And was there a feeling of exposure on putting such a personal story out into the world? “Not the way you might think, no. I don’t get much of that ‘Is this really true?’ thing that I think a lot of writers probably get. I found very quickly that people were not talking so much about the book itself; they were talking about their own grieving experiences.”

That special connection shows no sign of waning, as Girard discovered at the new edition’s launch at Librairie Drawn & Quarterly in September. “People were coming up to me saying ‘I lost my brother,’ ‘I lost my mother,’” he recounts, clearly humbled. “My day job is as a social worker at a hospital, so I work with a lot of emotions there, people dealing with trauma and disease and loss, and there I was at the launch, hearing some of the same things. It’s like my role is listening to people.” mRb

0 Comments