One of the delights of reading fiction is that it lets you travel at practically no cost to places you would otherwise never see. Of Water and Rock, Thomas Armstrong’s debut novel, takes readers to modern-day Barbados, but not the Barbados of glossy travel brochures featuring beaches and resort hotels. This is behind-the-scenes Barbados, in the private homes and lives of the locals.

For the most part, the trip is worth taking. Armstrong knows Barbados intimately. Married for over thirty years to a Bajan (the local term for Barbadian)woman, he currently divides his time between the Caribbean island nation and Canada. He takes pleasure introducing readers to Bajan customs like drinking fresh coconut water and Banks beer, or eating cou-cou and dolphin steaks barbecued by street vendors over sectioned metal barrels. He describes island flora in lush detail – the ficus and cottonwoods, the deadly manchineels and the ancient mahoganies from which Barbadian furniture is made. He speaks knowledgeably about limbo dancing, tropical storms, and obeah – a term used in the West Indies for folk magic or sorcery. He shows readers landmarks like Cheapside Market in Bridgetown, and less touristy spots like the corner rum shop.

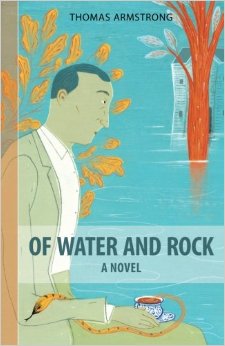

Of Water And Rock

Thomas Armstrong

DC Books

$19.95

paper

330pp

978-1-897190-59-3

The novel opens with a young White Toronto man named Edward Hamblin flying to Barbados to claim a property he’s inherited from the family of his estranged Bajan father. Edward has never been to Barbados before. He has mixed feelings about it, associating it with the man who abandoned him in childhood. Within a week of his arrival, he is adopted by a cast of colourful characters who make him feel more at home than he has ever felt in grey, impersonal Toronto.

But the voyage isn’t all fun and games. Edward unearths dark family secrets with implications for his own life as well as for relations between the local Blackand White communities. These relations, Edward discovers, still bear the scars of Barbados’s colonial past. Wealthy White landowners like Edward’s neighbour, James Collymore, continue to treat their Black countrymen with scorn.

Armstrong describes Collymore(whose name, incidentally, is that of a famous Barbadian writer) as an “obese older White man with a large nose and ruddy complexion,” whose handshake feels “like a dead wet fish.” His Black characters are more attractive. They include a poor but honest farming woman named Sissy; a prostitute with a heart of gold named Ginger; a madman, Doc, who speaks the truth in Sphinx-like riddles; and Sissy’s flamboyantly gay and open-hearted nephew, RJ. In a book that argues so cogently for nuance in race relations, the characters feel too starkly drawn. Whites from the Island tend to be bigots, and Blacks morally and spiritually unblemished.

Collymore and his daughter Mary, the novel’s worst sinners, eventually see the error of their ways, but lack the complexity to be fully convincing. So does saintly Sissy. The book’s greatest weakness, however, cannot be laid at the writer’s feet. There are a large number of typos here, including a howler in which Ginger pulls off her shirt, revealing “an under-sized brasserie.” And Armstrong’s prose, which is occasionally awkward and heavy on adverbs, could have used much closer editing. These criticisms aside, Armstrong has succeeded admirably in bringing to life a place that was once called “Little England,” where guests, we are told, are still offered high tea. mRb

0 Comments