Writer Maria Meindl inherited thirty-eight boxes of papers from her grandmother Mona Gould. Mona was a big name at one time, but, by the 1960s, she was virtually forgotten. Born at the very time that Mona’s career as a writer and broadcaster in Toronto was faltering, Meindl became her grandmother’s most admiring and loyal audience. Now Meindl has written a fascinating history of her grandmother’s brave attempts at living the life of a poet, and her own thoughts on life and freelancing.

Anne Lagacé Dowson: Some people are familiar with your grand-mother’s widely anthologized poem “This Was My Brother,” but few are aware of Mona Gould. Why a book about her?

Maria Meindl: My childhood memories of Mona are vivid and disturbing, just the type of experience that ferments over the years and draws the attention back and back until you express it in some form. As soon as I sat down to write anything, Mona was just there. I couldn’t not write the memoir sections of the book. Just before she died, Mona left her papers to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. I’d taken on the job of sorting them and it made sense that I should go on to write the biography. It was a real “should,” though, and at times I resented it. I waffled for a long time before I admitted to myself I was writing the book. Judge Edra Ferguson (who had known Mona from St. Thomas, Ontario) called me up after Mona’s obituary appeared in the Globe and Mail, and told me she would help me with the research, as if the book were already underway (even though at that point I was just coming to terms with the magnitude of sorting the papers). I found it impossible to say no to Judge Ferguson. That was a strong motivating factor! I’m glad I did it, though. All of it.

ALD: You lived in Montreal and the Townships – how did that influence your work and life?

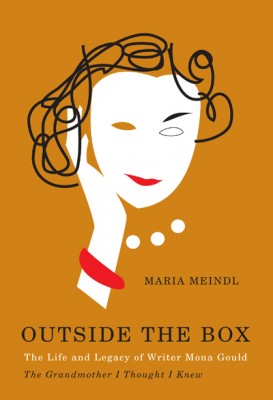

Outside The Box

The Life and Legacy of Writer Mona Gould, The Grandmother I Thought I Knew

Maria Meindl

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$34.95

Cloth

312pp

Uncorrected proofs

978-0-7735-3911-2

MM: I went to Bishop’s University, and moved to Montreal for a couple of years afterwards. I thrived there. It was a revelation to me, that there was a big world far away from the responsibilities I’d been carrying since birth. It was fresh, exciting, and mine. It was different enough (back then) that I felt like an expatriate, but also still part of Canada. I love Quebec and still go back regularly to visit friends and family, but it was really hard to find work in the early 1980s. Plus I felt a call – for better or worse – to come back home. I could not have put it into words at the time, but there was something I had to take care of or figure out here in Toronto. Mona was part of that.

ALD: What did you discover about the grandmother you thought you knew?

MM: Mona was a great spinner of yarns. Pretty much her whole life story had been – I won’t say fabricated – but vigorously massaged. She never talked about the diligent way she had built her career. Nor did she ever talk about how much other women had helped her. All those details were in her papers. Interestingly, I had more admiration for the grandmother I discovered in the boxes than the one I thought I knew.

ALD: Mona was a character – tell us about Jungle Red and picture hats.

MM: Jungle Red is the colour of nail polish the characters talk about in The Women by Clare Boothe Luce. In the play, the colour symbolizes the willingness to scratch another woman’s eyes out! Mona loved all that stuff, and she affected the Joan Crawford look with the big hat and the red lips painted to look squarish. All these trappings served as decoration, a protection, and as a kind of battle dress in the war she felt was constantly underway among women. As life went on, she started to resemble Norma Desmond from Sunset Boulevard. I don’t think that was intentional, but I don’t think she would have minded people saying so either!

ALD: She was inspired by Dorothy Parker and admired Katherine Mansfield – how did they influence her?

MM: Mona’s witty verses were directly inspired by Dorothy Parker, and Mona was also brilliant at writing them. Katherine Mansfield was an idol, too, though Mona was unlike her except perhaps in looks. She patterned herself after these women, and the myths she wove about herself were drawn from their lives. Edna St. Vincent Millay was another one. In her day, Mona didn’t have many role models in her own country, and she had a tendency to look outside rather than in, period. The introspection only came later in life when she was struggling emotionally and financially. Ironically, I think her poetry benefited from those difficulties.

ALD: You say that Gould spent her life fighting failure, hiding the fact that she was always a step away from poverty and obscurity – why is that?

MM: She really believed that she could earn her living as a poet. Need I say more? Still, I love her for never giving up on that quixotic dream.

ALD: She knew P.K. Page and Dorothy Livesay – why did she not become as well known?

MM : Sorry Mona, wherever you are but … Frankly, she wasn’t as good. She didn’t edit herself or let herself be edited rigorously. She didn’t do the really tough, demanding part of the job, and it shows. But on the other hand, who cares? Mona defined herself as a popular poet. That’s something that doesn’t exist any more. A certain academic snobbery around poetry came slamming down after the war and Mona suffered from it. She wanted to write a lot, and be read a lot. She wanted to touch people and speak to the important occasions of their lives in a way that gave them an outlet for their own feelings. At this, she was a brilliant success. She established venues – radio, magazines, newspapers – to share what she wrote. She got sheaves of fan letters. For her poetry! Times are changing, though. I do believe her work will come back into favour because it’s very moving, especially when read out loud.

ALD: The poem she is best known for contains an element of anti-war sentiment – what were Mona’s political views?

MM: Later in life, she used to read the poem to school groups, along with the slogan Make Words Not War. She thought war was a terrible thing, to be avoided at all costs.

ALD: Dieppe is now considered to be a butchery – how did Mona cope with the loss of her brother?

MM: That’s a complicated question. Even though she was a staunch pacifist, she never, never addressed the dissention that surrounded Dieppe. At least, I never heard her do so. It came out clearly in her papers that Mona was under pressure from editors to put her emotions aside throughout the war. The poem seems all the more skilful in light of this because in the final couplet, she walks a fine line, and gets away with it. The poem was very widely distributed. I think it cost her a lot to keep her feelings under wraps, though, and I don’t think she ever recovered.

ALD: One of the reasons you wrote the book, and took the time to catalogue Mona’s papers, is because there is little documentation of the life of Canada’s literary freelancers. How does her life resemble and differ from yours as a freelancer?

MM : There’s one big thing we have in common: fatigue. But don’t we have that in common with all women? I loved coming across letters about Mona’s busy life and that of her friends. I felt a kind of solidarity across the generations. As for differences, at one point I kvetched in my blog: “Mona got the martinis, I get the footnotes.” It always seemed like she had more fun, particularly when it came to the gruelling work of sorting her papers. Also things are getting harder and harder for writers. The 1950s were really good times for freelancers. One could make a living. Even so, Mona was constantly stretched to the limit and spent her old age in poverty.

ALD: What are today’s freelancers to think based on your and Mona’s experience?

MM: When David Mason appraised the collection he wrote that there’s little documentation of the lives of Canadian freelancers and I do think it’s an important thing to think about because history can help us gain perspective on the present. Even though Mona scorned material things she must have known deep inside that she was living through important times and that her “stuff” would be valuable some day. Otherwise she wouldn’t have kept it.mRb

0 Comments