Last year, when François Bouvier’s film adaptation of Michel Rabagliati’s Paul à Québec was about to reach the theatres, more than one Rabagliati devotee of my acquaintance expressed severe apprehension about the project. Fans have a way of getting territorial about their heroes, but in this case you sensed a stronger than usual concern. Rabagliati is arguably Quebec’s most beloved cartoonist, and Paul, the star of his autobiographical graphic novel series, has come to feel like the readers’ friend; his world, their world. What if the movie – a live action movie, at that – messed it up? Well, they needn’t have worried. The film was a delight, and I think I know why: the work, in a real sense, had already been done. Make a reasonably faithful representation of what Rabagliati has put on the page, as Bouvier did, and you can hardly go wrong.

Paul Up North is the eighth volume in the Paul series. Rabagliati says it might be the last, and if that turns out to be true, we’re leaving at an odd juncture. The new book disdains straight chronology to take a nostalgic trip back to the Olympic summer of 1976; Paul is an awkward, frequently surly adolescent discovering love in the Laurentians when he isn’t hiding out in his bedroom at home. Montreal’s East Island suburbs come in for a tough ride, but the disdain Paul expresses for SaintLéonard and Anjou is not reflected in Rabagliati’s meticulous, attentive treatment of them. Investment like this can only come from a place of love, and the same applies to everything he sets his sights on.

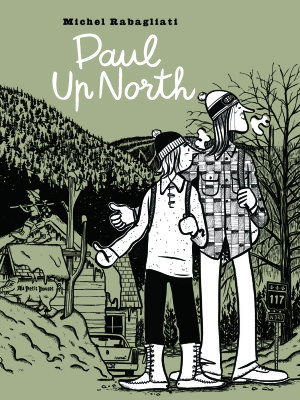

Paul Up North

Michel Rabagliati

Translated by Helge Dascher

Conundrum Press

$20.00

paper

184pp

9781772620016

Perhaps surprisingly for a book set at the height of nationalist feeling in Quebec, politics get a direct nod only once, when a driver who picks up Paul and a friend hitchhiking rails “Anglos have been shittin’ on us for centuries, tabarnac!” That the boys don’t respond isn’t surprising: they’re self-absorbed in the eternal matter of male teens, and besides, Rabagliati prefers to present his social history more obliquely, through the details. Newcomers to Quebec rock culture, for example, will get a crash course in bands whose profile barely spread beyond the province’s borders but were icons here: Beau Dommage, Offenbach, Octobre, Lougarou. Rabagliati knows nothing triggers memory quite like music, and he treats it suitably seriously.

If you were a teenager in the 1970s, Paul Up North will be the closest thing to time travel. If you weren’t and want to know how it was, it will tell you as much as any novel, record, or movie – in fact, it will tell you more, being a perfect blend of the three forms. If this really is the last Paul book, it will be interesting to see what Rabagliati does if he gets around to looking back at our Quebec present in some other form. Because if he wants to be truly accurate, whatever he does will need to have at least one of his own books somewhere in it. mRb

0 Comments