The Smooth Yarrow

Susan Glickman

Signal Editions

$18.00

paper

78pp

978-1-55065-330-4

Susan Glickman’s book, The Smooth Yarrow, shows a chilling awareness of mortality through the accumulation of injuries like broken bones and the loss of teeth. Not old yet, she is close enough to celebrate elderly women “who use their best china every day / and jump the queue at the grocery store because they have so little in their baskets / and no time to waste.” Even her garden poems mix exquisite celebrations of new life with knowledge of the transience of beauty. The first section of her work is called “Homeopathic Principles.” Whatever the truth of homeopathy as a medical practice might be, the philosophy of treating an illness with drugs that induce its symptoms is – suggestive. A poem can build up our resistance by administering mild doses of the very toxins that we suffer from in living: sickness, age, grief. The loss of a loved one is the greatest toxin of all, and Glickman’s elegy for her father, “Breath,” offers not consolation but a powerful recreation of his passing, with the breath of the dying man as the focal point for a family unsure how to react. Emily Dickinson’s great poem, “I heard a Fly buzz–whenI died” comes to mind, but the confusion in Glickman’s poem is in the watchers, not the person dying. “We hesitated, no longer sure what to pray for.” Uncertainty is the paradoxical remedy here, evidence of how deeply the family cares. The poem that deals explicitly with homeopathy as a metaphor is “Homeopathic Remedies for Scar Tissue.” Glickman knows that life is a series of scarring experiences. One remedy is to smear sandalwood paste on the injury. It will attract bees, from which we may learn how to dance in the sun and how to fight back, though a bee’s self-defence is fatal. But life is fatal, after all. In one of her excellent garden poems she celebrates the compacted hearts of rosehips (analogues for the mature poet), and calls them “Late bloomers: late / as in late Brahms. Not tardy / but ripe.” The analogy with the great autumnal works of Brahms is a good one and also fits Glickman’s own wise and elegant work.

The Major Verbs

Pierre Nepveu

Translated by Donald Winkler

Signal Editions

$18.00

paper

72pp

978-1-55065-339-7

Pierre Nepveu’s collection of poems, The Major Verbs, translated skilfully by Donald Winkler, is also wise and elegant. A Montrealer, he has won the Governor General’s Award three times. The third section of his book, “Exercises in Survival,” is his expression of filial piety, an elegiac sequence about his parents. It is not surprising for a poet of the Baby Boom (he was born in 1946) to approach this subject. Piety does not exclude frankness, however, and he documents his conflicts with them over religion. He knows that family conflicts are small on the cosmic scale, that we “wound ourselves bravely / with kitchen implements,” but grief is not trivial in spite of the domestic metaphor. It forces us into the realm of major verbs. He says: “to be born, to grow, to love, / to think, to believe, to die.” The alternatives to these experiences are quietism (to live in the infinitive, unconjugated, and therefore immobile), or, in a similar way, to retreat into the self so far that the verb “to go” no longer has meaning. The elegy for his parents is followed by a celebration of the universe: a poem modeled on the great Navaho chant, “We walk in beauty.” The implication is that the catharsis of grief leads to a new perception of harmony in life. The rest of Nepveu’s book is cast in two sequences: a meditation on a handful of stones (the subject is really the loss of a lover) and a brilliantly empathetic set about an immigrant woman who has fallen asleep on the subway after a night of menial labour. Nepveu’s work shows variety and fulfills his own goal of writing with the major verbs.

For as Far as the Eye Can See

Robert Melançon

Translated by Judith Cowan

Biblioasis

$19.95

paper

152pp

978-1-927428-18-4

Robert Melançon’s brilliant book, For as Far as the Eye Can See, originally published in 2004 as Le paradis des apparences : essai de poèmes réalistes, is about art and perception. His tone is detached in comparison with Nepveu and Glickman, but art has many mansions and therefore many windows on reality. The poems, which he calls “light sonnets,” are twelve- line units, each in four stanzas. There are 144 altogether: twelve times twelve, and each is numbered. The poems function like window frames, he tells us in number 36: they are “lesser sonnets” and their shape is rectangular. The narrator makes a few trips in the city, but mostly he observes and paints (his favourite metaphor) “the paradise of what I see,” mostly skies, streets, and walls. His seeing is inspired by artists, not poets: he cites Claude, Turner, O’Keeffe, Caravaggio, Brueghel, Poussin (his closest affinity), Hals, Friedrich, the Cubists. He also admires the clear and cerebral piano music of Glenn Gould. Mostly he is interested in urban landscape, but now and then he retreats from the window perspective and creates a still life (nature morte). The point of view in the book is so consistently confined to a room that it becomes a little claustrophobic, and the reader is relieved to follow the narrator out to a poetry reading and a book launch, both presented humorously. He provides two poems about unwashed street people as if to show that he is aware of what Wordsworth called “the reek of the human.” One hundred forty- four poems of acute observation: Melançon’s invention is impressive. Judith Cowan’s rendering of the poet’s work into English is adroit and fully idiomatic.

A Rhythm to Stand Beside

Jack Hannan

Cormorant Books

$18.00

paper

96pp

9781770862463

Some of Jack Hannan’s poems in A Rhythm to Stand Beside are not written but generated. The biggest effort is “A brush through a mathematical selection of G,” a work that required selecting words from John Berger’s novel G, and then writing a poem using only that selection. Another poem, “Cirlot’s cross,” is “made up of words and phrases that were taken from an old edition of Cirlot’s Dictionary of Symbols.” In his original poems, Hannan still generates a great deal of verbiage and the reader can grow impatient with the sheer quantity of language delivered with a whimsical tone. He is often at his best when he violates the norm of conceptual poetry and employs anecdotes. John Cage is the godfather of this kind of generated poetry. Generated or manufactured? It is easy to be skeptical, but our leading conceptual poet, Christian Bök, once said at a poetry reading that “today’s noise is tomorrow’s music.” It is possible that Hannan’s constructions will seem musical tomorrow. But he needs to keep the major verbs in mind.

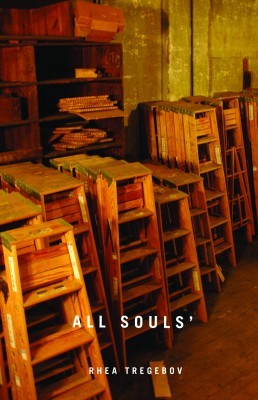

All Souls’

Rhea Tregebov

Signal Editions

$18.00

paper

78pp

978-1-55065-338-0

Rhea Tregebov’s work, All Souls’, is today’s music and very listenable. Like Glickman, she is clearly (and admits to being) “of a certain age” and aware of the infirmities of the body. Both poets were born in 1953, baby boomers like Nepveu. Boomers don’t need seminars on retirement; they need seminars on caring for what a Dickens character affectionately calls the “Aged Parent.” Tregebov laments the aging of her parents in a series of poems focused on family dinners, a very effective strategy for exploring the intimacies of relatives over a long period. The last family dinner is a brief glimpse of the father cinched in a Geri Chair near the nurses’ station, courteously offering to share his Spanish rice. The brevity generates the pathos. The concluding poem, “Abundance,” is a stunning look at the Old Jewish cemetery in Prague, where the dead were buried in twelve-deep layers. The title of All Souls’ hits home with this scene of community in death. “The streets of the living are among the streets of the dead,” the poem says. The Book of Common Prayer puts it in a similar way: “In the midst of life we are in death.” The tragic history of the Jews in Prague is the unspoken background of the poem. The conventional image of grapes on a tombstone is an ironic symbol of abundance in an area packed with the dead. Another gravestone, commemorating a tailor, has a pair of shears, perhaps an echo of the shears of the Fates. On a less sombre note, Tregebov’s gardening poems (Boomers like to garden, it seems) are excellent. She also has three fine works about spices. She tells us that vanilla, which is used to flavour white ice cream, comes from the blackest of fruits. With such paradoxes the poet flavours the world. mRb

0 Comments