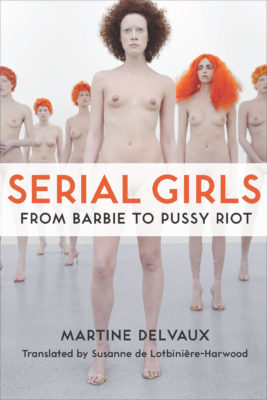

What does it mean when images of femininity are staged as near clones or repeating figures? That’s the question novelist and UQAM professor Martine Delvaux tackles in Serial Girls: From Barbie to Pussy Riot, recently translated into English by Susanne de Lotbinière-Harwood.

From Barbie dolls to Playboy Bunnies, there are legions of undifferentiated women presented as a group or type, usually sharing a name. Dubbing these serial girls, Delvaux argues that the trope is structural and normative, imposing a generic femininity: it is “not about shaping girls as they are; it is about shaping girls into what we want them to be.”

In these systems, female figures become nearly identical and interchangeable, choreographed to move in sync as part of a seductive “geometry” – think of a Busby Berkeley number, cheerleading routine, or cancan line. Serial girls are framed as ornamental compositions rather than as individuals, which Delvaux argues makes them titillating but inaccessible. Lacking individuality, they become thing-like, commodified for easy consumption, and prone to violence: both the symbolic violence of nonrecognition and the actual physical harm that befalls those whose identities don’t matter.

Serial Girls

From Barbie to Pussy Riot

Martine Delvaux

Translated by Susanne de Lotbinière-Harwood

Between the Lines

$26.95

paper

184pp

9781771131858

Non-cisgendered people and women of colour get short shrift in Delvaux’s analysis, a glaring omission given the aspirational whiteness inherent in the serial girls she describes and a missed opportunity to enrich her analysis by considering how racism, transphobia, and heteronormativity structure these formations. Delvaux’s position on men is also oversimplified; there’s no need to dismiss how boys are oppressed by structural gender norms while choosing to focus on the ways that girls are. It’s a shame, too, because contrasts in how gender is performed in groups set the stage for some of the book’s more interesting moments, such as an account of how choreographed spectacles of women complement men’s military formations to provide the pageantry that makes fascism palatable.

The topic of Serial Girls is cool and ambitious, but the book offers little accessibility to an audience beyond academics and already-convinced old-guard feminists. The work is strongest when Delvaux turns to serial girls’ revolutionary potential by championing figures who express idiosyncratic and politically charged femininity, pointing to Femen, HBO’s Girls, and Pussy Riot. She holds that the serial girls are a motif that allows femininity to be invented, so while uniformity encloses girls within imposed generic standards, refusing these hegemonic images creates spaces where marginal modes of being can proliferate, where individuality becomes self-constitution. Citing work by scholars of exception like Giorgio Agamben and Deleuze and Guattari, she finds hope in serial girls when they step out of the roles they’re assigned, in all of their messy specificity.

0 Comments