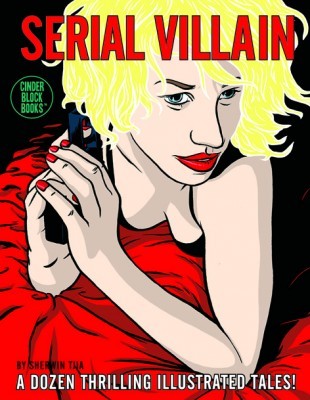

Serial Villain is a cross between a short story collection and a comic book, written and illustrated by the prolifically un-pigeonhole-able Montreal artist Sherwin Tjia.

The collection of “A Dozen Thrilling Illustrated Tales!” works the noir genre in a style that is heavily informed by contemporary crime drama. Every third or fourth page of the book is a black-and-white illustration that depicts action scenes with purposefully gauche stiffness – think pulp novel covers done in comic strip flatness. The stories are driven by plots that ask questions like what if an assassin travelled back in time to kill Hitler’s parents but fell in love with his mother, or what if a serial killer was being tormented by the ghost of one of his victims? Tjia’s willingness to escalate the action and take these concepts to – and beyond – the extents of their natural limitations is the collection’s strongest point.

Character details and motivations are what give short stories their texture, but Serial Villain uses the tics of individuality to justify its plot twists; the bodyguard’s brother who kills their mutual client says, in the middle of a car chase, “I’m in over my head Tim. I owe some very dangerous people a great deal of money… It was the gambling.” Dialogue exposition is done this way in TV and film for scene economy, but print is not governed by the same pacing or visual constraints. The gambling debt is an opportunity to define the tone and fabric of the story, but this revelation is hard to accept when it pops up like a jack-in-the-box at an implausible point in the action. The stories would be richer if these threads were woven in earlier, and more thoroughly integrated with the illustrations.

Serial Villain

Sherwin Tjia

Conundrum Press

$17.00

paper

360pp

978-1-894994-67-5

The collection’s inventive plot devices and cinematic pacing show enormous potential. The illustrations define their own style and tell their own stories. Serial Villain is clearly smart, like the kid at the back of the class who doodles inventively disturbing scenes in textbook margins, but in a world where senseless violence and graceless sex are easy to find, this collection does little to add to either theme or improve our relationships with them, and ends up feeling like just another scream in the cacophony. mRb

0 Comments