Sans amour on n’est rien de tout. So sang Edith Piaf, whose love life was notoriously unhappy. The lyrics haunt the heroine of So Long, Louise Desjardins’ third novel.

Love is a central theme in Desjardins’ writing. The title of her first novel, which won the Grand Prix du Journal de Montréal in 1993, is La Love, and her subsequent books (two novels, a memoir of singer Pauline Julien, and a story collection entitled Coeurs braisés) continue to explore the subject. In So Long, first published in French in 2005 and now available in an English translation by Sheila Fischman, the narrator/heroine is obsessed by it.

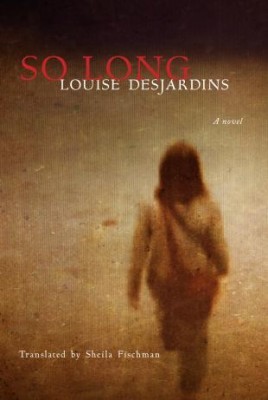

So Long

Louise Desjardins

Translated by Sheila Fischman

Cormorant Books

$21

paper

144pp

978-1-897151-90-7

Love and freedom are the novel’s poles: two powerful, opposed forces. In Katie’s life, freedom has definitely won out. Recently retired, twice divorced, with two daughters and additional stepchildren grown and gone, and with several failed love affairs behind her, Katie now lives alone in a tiny apartment on Fullum Street (an ironic name, given her life’s emptiness). “I lose everything,” she admits early in the story. “My daughters. My husbands. My plants. All that’s left are some books, a few paintings and a whole pile of things brought home from travels.”

As the novel opens, Katie is sitting on her bed performing a birthday rite of reviewing her journals and taking stock. The journals provide a portal to the past, allowing Desjardins to flip back and forth in time between the stark winter day and Katie’s richly peopled past. The best chapters describe her childhood in Abitibi, where her philandering father owned a music store and played the fiddle in a local bar. When the gold mines are shut down in 1944, just before Katie’s birth, her father shuts his eyes to economic reality and refuses to leave, braving bankruptcy and clinging to an “impossible dream” that one day the mines will reopen.

Like her father, Katie clings to the past and dreams of improbable futures. Instead of gold, her focus is love. After Abitibi, beautifully rendered by Desjardins, a native of the area, we move on to Katie’s marriages in Montreal and the daughters she bears to different fathers. We meet the stepchildren too, wounded by the mess their parents have made of love, and we encounter Katie’s poetry-writing, pot-smoking lovers. We see the grade school where she used to teach, and the girlfriends, single and middle- aged like herself, who spend their hours trolling the Internet for men. Katie does the same.

Compared to Katie’s richly imagined past and future, her present is depressingly thin. This may be Desjardins’ point: at a certain age, our lives empty out, leaving mainly memories and dreams. This may or may not be true; but fiction needs drama, and Desjardins does her best to fill the hole at the centre of her story. She inserts a party, organized by the daughters, to which Katie’s exes and stepkids are invited. And she brings a cyber lover from Winnipeg to Montreal for the occasion, placing past and future on a collision course with Katie’s insubstantial present. There’s great potential here, but in the end, Desjardins doesn’t deliver. Like Y2K, So Long ends not with a bang, but a fizzle. mRb

0 Comments