perhaps that

perhaps there

perhaps another where there was

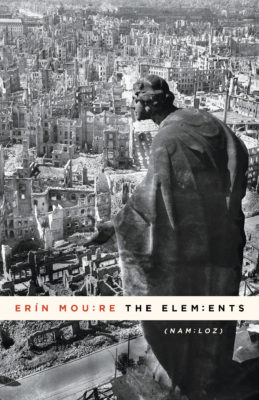

— Erín Moure, The Elements: (Namloz)

Erín Moure’s The Elements: (Namloz) begins, shoulders back, index finger up, with the words “In fact.” This gesture is a complex one because of the way Moure shifts between battle scenes, theory, and philosophy. In the opening prose poems of The Elements, Moure’s eighteenth book of poetry, this gesture – this phrase – signals that facts are inextricably linked to real bodies: “Pain felt by the body is thus a task for history.” Likewise, it is clear that facts are subject to the experience of being (and Being!), subject to how we remember, or more precisely for Moure, to how “we are remember.”

This line “we are remember” in part reads as reassurance for Moure’s father, as well as Moure and her siblings, as they experience the way his memory changes because of dementia. But this line also points to the how of memory, how one might be remember. This is one way to think oneself through The Elements, which, though it is not an elegy, is a generous exploration of losing a parent. It is an examination of the histories, interests, and knowledge that are transmitted between generations. Even more so, however, in this book Moure collaborates with the idea of transmission. She explores what history and what of oneself can be shared when these things must inevitably be translated. She negotiates with the capacities of language and memory, acknowledging the way these elements shape us as much as we shape them. It’s a collaboration because, as Moure sums up one section, “in other words, language estranges the human and we let it utter us.”

The Elements

(Namloz)

Erín Moure

House of Anansi Press

$19.95

paper

120pp

9781487003722

Already the structure consumes me. I may write in any language I like, as long as it is Castilian or English. And so I am already speaking to you in translation, in a foreign tongue, slowly.

Later, in “And what of”:

And what of the grammar we were griven those years

or the one we invernted

elaborate, full of beasts of the stupendous cortex

crawpling

The misspelled words are deleted, but not really. They are maintained with a reference to deletion. Words that do not fit into the structure become ghosts haunting the grammar of the poem. That is, one may, and almost certainly will, read these lines with and without the almost-deleted words. So while the structure may consume the speaker, this is just one example of how these poems are themselves possibilities, simultaneously offering multiple structures for the writer’s (and reader’s) thoughts to inhabit. It is a way of working with language even if you understand language to be working you.

It is not only how memory and thought fit and un-fit into structures that is significant, but also where they are in space and time, and how they travel. Writing and being remember become spatial tasks; they become mappable. Later, indeed, a scan of a map of north-west Spain appears, showing where battles were fought and the movements of the Galician army in 1808-9. On this map, broken lines are retreats and unbroken lines are advances, the movements of bodies are recorded and thus the connection between bodies/locations and inscription/writing becomes a document of history and fact, which is what makes this connection both urgent and transmissible.

Finally, although there are many more ways to break down and appreciate the poetry of The Elements, it is worth noting its textures. Moure employs prose blocks, lyrics, her characteristic playful language (say “Ayam Wotayam” aloud, for example), scans that “were decided by a printer that crashed pagescapes from Derrida’s ‘How to Avoid Speaking: Denial’ beneath poems from The Unmemntioable,” as well as transcriptions of found documents (including a translation of a poem from Little Theatres by Moure’s father). This is a formally exciting work that, for me, hinges on the idea of perhaps, that is, what we know possibly but not certainly. mRb

Author photo by Karis Shearer

0 Comments