“I remember reading that, for some, having had a happy childhood is almost as painful as having suffered an unhappy one,” muses the narrator of The Girls of Piazza d’Amore. “It feels like a persistent ache of yearning, like the grief for a lost love.” The novel draws extensively on writer Connie Guzzo-McParland’s own youth. Using her childhood experiences as a springboard, Guzzo-McParland tells of the changes in a fictional village in the south of Italy in the years after the Second World War and of a family preparing to immigrate to Canada in the 1950s.

The Girls of Piazza d’Amore

Connie Guzzo-McParland

Linda Leith Publishing

$13.95

Paper

161pp

978-1927535196

“Painful but ultimately liberating,” she describes the editorial process.

In The Girls of Piazza d’Amore a woman retells the stories of her childhood in Italy before settling in Canada. Caterina describes a sleepy, slow-moving world in which locals eagerly await the arrival of the mailman twice a day, women clean their laundry on concrete washboards by the river, and church functions are at the centre of the social sphere. Men habitually leave their families behind to find work and the children play in simple-minded bliss.

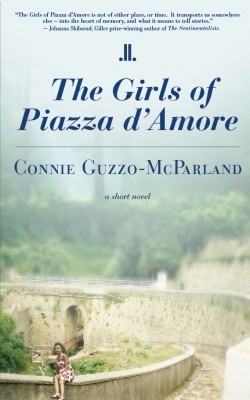

The title and cover design suggest a simple romance novel, with a young woman reclining on a cement partition and a distant landscape that softens to a soothing pastel blur, but the book is more than that: it is a vivid portrait of life in a restless community; a window into an isolated world replete with eccentric characters. These include old Anna, crazed with grief after losing her son in the war; Professor Nucci, a thirty-year-old bachelor living with his spinster sisters, who spends his days walking up and down the streets with a baton; and Don Mario, a man half paralyzed in battle who rarely emerges from his home.

The adults struggle with claustrophobia and the after-effects of the war, but for the children the town of Mulirena is a far more benevolent place. “It’s like a paradise lost,” Guzzo- McParland describes it. “Sometimes it can be painful to think you can never regain that place. The children in the village were really cherished.” In writing The Girls of Piazza d’Amore, Guzzo-McParland aims to capture that loss and to commemorate her youth in Italy.

Her prose often captures the sense of something just out of reach: “The men gorged themselves on the first ripe figs of the season, savouring the juicy red pulp while looking up at the girls with yearning eyes.” Some of the writing is funny: “The two villages were like Siamese twins joined together at the neck but wanting badly to keep their distance from one another. If one village sneezed, the other, jolted by the vibrations, would sneeze back harder.”

At times, however, The Girls of Piazza d’Amore feels more like an elaborate mosaic of images and stories than a novel. The tales are laid out in the book one after another, and though the quiet village setting lends itself well to Guzzo-McParland’s anecdotal approach, these are occasionally disconnected. Major and minor events are given similar weight, and many of the vignettes have no overarching narrative function. To wit: a monumental event like a suicide attempt is described in one paragraph, as if an afterthought, while a gypsy girl stealing a book goes on for several pages, in spite of its irrelevance to the plot.

This approach is interesting, and it is certainly intentional, but it comes at a cost. Writer George Saunders once commented that the hardest thing for fiction to do is to create steadily rising action – something missing through much of The Girls of Piazza d’Amore. With little suspense and a kind of absent-mindedness about the flow of stories, this work might have been stronger as a collection of short stories.

Though many are quite mundane, the stories are appreciably different from those of modern life. Many could stand alone, including three that recount the casting process of a church play, the arrival of a new teacher, and a visit to the beach. Caterina is especially taken with the illicit romances that happened in a setting where “women were criticized for so much as speaking to a man who was not a close friend or relative.” She describes how the girls look out from their balconies as suitors linger below and occasionally the men are doused with dirty dishwater thrown over the ledge by a disapproving family member.

Caterina especially loves to follow Lucia and Aurora, “two of the prettiest girls in the village,” and Tina, who is “always cheerful and liked telling jokes.” All three are courted by dashing young men, though Lucia’s tumultuous romance with Totu, which picks up towards the end of the novel, is the only one to hint at anything like a sustained plot. One of the failings of The Girls of Piazza d’Amore is that Lucia and Totu are among the few characters to recognizably change over the course of the novel.

Caterina herself never grows up to experience Calabrian romance first- hand, since, at the time, families in the village were steadily leaving to find work and money elsewhere. “There was just no opportunity,” Guzzo- McParland says. “That was one of the main problems – unless you were a farmer and worked the land, the men had to leave the towns.” Many Italians were sponsored by family members in Canada, where it was much easier to build a life than in the tremendously expensive cities in the north of Italy. As time goes on Mulirena dwindles from its original population of 1500. “‘Four houses and four cats,’– that is how we spoke about [Mulirena] after we left,” Caterina explains.

Though earlier iterations of Guzzo- McParland’s novel included stories of life in North America, in The Girls of Piazza d’Amore Canada looms over the novel as a vague, unreal place, a foil to the familiarity of life in the village. As her schoolteacher describes the immensity of the country, Caterina explains “the word ‘immensity’ took on the shape and colour of the silent forests of Canada. There was no mention of cities or people, as though Canada were only land and water.”

It’s a respectable debut novel, one that invites the reader into the landscape of Guzzo-McParland’s memories before immigrating to Canada and the experiences of a youth that can never be recovered. In spite of some of its disconnects, hers is a poignant portrait of a simple world fated to change and the idyllic times of childhood that, however remote, none of us can quite manage to leave behind. mRb

0 Comments