The first novel by second-generation Korean Canadian Christina Park, The Homes We Build on Ashes, explores key aspects of the Korean experience, from the mid-twentieth century to the present. A work of fiction inspired by Park’s grandmother, the story is primarily that of Nara, a woman who repeatedly rebuilds her life in the face of significant hardships in Korea, then Canada.

As a girl and young woman, Nara saw her life all but destroyed under Japanese occupation, including during World War II, when she becomes a forced labourer in a factory. She endures the Korean War’s violent era of suspicion in a refugee camp, then a catastrophic, city-wide fire, before migrating to Vancouver in the early 1970s. Nara encounters racism in Canada, but her most profound struggles here are centred around troubled family relationships and an inability to reconcile with her past.

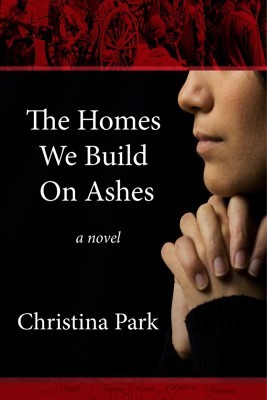

The Homes We Build on Ashes

Christina Park

Inanna Publications

$22.95

paper

264pp

9781771332330

This is a tragic tale constantly searching for peace, and as such, neat, satisfying connections and conclusions would be out of place. Even so, The Homes We Build on Ashes often loses its way because of a lack of cohesion.

By occasionally including other characters’ perspectives, Park certainly adds nuance. However, this always feels awkwardly welded onto Nara’s story, even haphazard at times. There are meditative passages variously driven by Buddhism, Shamanism, and particularly Christianity, as well as psychological insights and observations about oppression, resistance, conformity, and social order, but little sense of the novel’s overriding philosophy. Symbols – a cooking pot, a tree – and points of connection, such as the deaths of two characters in similar circumstances, years apart, are piled on with so much other poorly developed material that their impact is diminished.

Perhaps even more fatal are the frequent language problems, which are not limited to a sometimes breathless excess of adjectives, hyperbolic similes, (occasionally mixed) metaphors, and cumbersome word repetition that could easily be solved with a pronoun. The frequent typographical errors are distracting, but worse are the failures to grasp a word’s nuanced meaning, such as when street peddlers are said to “heckle” Nara, though in fact they try to gain her attention with desperate politeness. Numerous misused words and bewildering phrases and sentences compound the sense that this book lacked adequate editorial oversight.

Undoubtedly, The Homes We Build on Ashes is an interesting novel, which sheds light on the Canadian immigrant experience and significant moments in Korean history. Park succeeds in building a strong, sympathetic protagonist in Nara, keeps the narrative moving along with several scenes of genuine drama, and expresses some ideas with poetry and insight. However, it is no credit to either author or publisher that it was released in this form, so clearly in need of at least one more draft to iron out the kinks. mRb

0 Comments