The Obese Christ by Larry Tremblay is a disconcerting book – and that’s exactly what it intends to be.

Edgar is a man who will elicit virtually no sympathy from readers, which is refreshing given current exhortations to build empathy for characters (or, rather, it would be if Edgar weren’t so relentlessly creepy). This reclusive cutter is not the Wolf of Wall Street kind of sociopath people are supposed to despise, but secretly seem to revere. Rather, he’s the kind who finds Helplessness, but feels no Samaritan compunction. Instead he locks it away, chains it to his dead mother’s bed, and treats it as an idol to be worshipped, as a pet to feed and control.

Again, the creepiness is not just intended, it’s engineered. The entire book takes place in Edgar’s warped mind and from his point of view. Three dozen scene-driven chapters, each two or three pages long; dense in their depiction of a man’s confusion, lucid and clear as a chair dragged across the linoleum floor of a quiet kitchen. And though he talks to people, there’s not a single dialogue exchange in the entire book. This dehumanizing device depicts the way Edgar uses others solely to enact his mutating justifications as he moves from rescue to kidnapping to murder to exorcism – it’s dreadful, but incredibly effective as a technique. There are not many books that make this reader’s flesh crawl, but The Obese Christ is undoubtedly one of them.

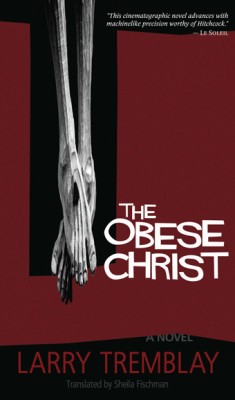

The Obese Christ

Larry Tremblay

Translated by Sheila Fischman

Talonbooks

$14.95

paper

144pp

9780889228429

In this way, perhaps he’s a more accessible type of monster, one suited for a macabre modern fairy tale. Instead of a wolf or a dragon or a vampire, Edgar is a grossly and poorly adjusted human being, seemingly impervious to the norms of society. He’s the reason why parents don’t let their children walk home alone from school – or at least the idea of him is. One can debate whether or not society needs another reason to be afraid of strangers and to put space between citizens, but there is no moral in this book, and neither is there moralism. There is no instructive desire, just a brief and fetid wallow in the mind of a very sick puppy, executed with composed atmosphere, dread-stretching pacing, and consummate control. If it sounds like your kind of fun, you’ll be hard pressed to find better … though you might not let the kids go trick-or-treating alone this year.

0 Comments