One of the downsides of being a lifelong reader is that one rarely approaches a book innocently, free from the spoiler effects of hype and reputation. I was out of the country, away from the news this summer, when Peter Behrens’ novel The O’Briens came to me in a near pristine state. His first novel, The Law of Dreams, won a Governor General’s Literary Award, but literary prizes being only a hair’s breadth away from a lottery, that meant little. It was the promise of a brick-sized tale spanning many decades in the life of a big Irish Montreal family that piqued my interest, and Behrens delivered beautifully.

It’s 1887, Pontiac County, an English-speaking community on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River, teenage Joe O’Brien and his four younger siblings are waltzing to the Victrola of an exiled New York Irish priest who has taken the orphans under his wing. The rest is about how Joe welds that advantage to a hard core of ambition fuelled by poverty and his father’s abandonment of the family. How he seeks out and marries a woman who will provide their children with a civilized upbringing while he devotes his energy to earning money. And how the scars of struggle are worn in later life.

Behrens follows his many characters with the dogged passion of an aged aunt bent on hunting down and revealing all the juicy parts of life. The patriarch fades in and out of the focus. Sometimes we are taken into Joe’s tortured psyche; elsewhere, he is observed from a distance, appearing to those who live with him – and the reader – cold, aloof, indecipherable.

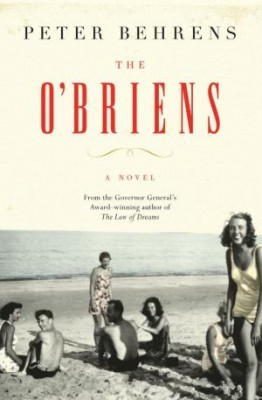

The O’Briens

Peter Behrens

Anansi Press

$32.95

Cloth

514pp

978-0-88784-229-0

The O’Briens is very much a study of character, and there are many great ones: Gratton, the occasionally irresponsible second son, free of Joe’s sense of responsibility, thus lacking his focus; Tom, the obligatory priest, estranged from the worldly ambition that spurs the main branch; Iseult, the woman Joe loves and yet does not understand; their children, as com- plex and unwieldy as their elders.

This is the story of a family’s progress from poverty to bourgeois ease, a mansion in Westmount, and enough money to make the idea of divorce in the 1930s not only possible, but comfortable. Then the brutal democracy of war, exposing the young men to battle and their women to worry and waiting. Behrens is a diligent researcher. Leaving the personal for public history, he inspires confidence with deft descriptions of how Joe makes his first fortune in railroads, what Montreal is like for a successful postwar industrialist, and how a wealthy, Catholic family participates in the Francophone world without ever fully crossing over.

Although social history isn’t its purpose, The O’Briens gives a fine picture of Anglo Montreal before the Quiet Revolution, a subtle yet important corrective to the stereotypical images thrown up by a more politicized time. The wartime chapters are reminiscent of Gwethalyn Graham’s 1944 novel, Earth and High Heaven, except that Behrens injects a dose of existential angst into those romantic times, to create a contemporary sensibility.

Some reviewers have found that the novel loses steam in the last third, where the story approaches living memory. I thought Behrens did a fine job of finding a fresh idiom for times closer to our own. Conveying events through letters, snippets, brief scenes, quick changes, the various episodes appear like a series of photo- graphs, from sepia to crisp black and white to Kodak colour. As the third-generation O’Brien children grow up, both the family and their story fragment into competing narrative lines, as they would in life. The final chapter is thrilling and poignant. A narrow escape for the patriarch, the ending could easily have turned tragic, making this a better book but probably not a more popular one.

Behrens’ first novel, The Law of Dreams, was written during a lull in the fifteen-year labour of bringing The O’Briens to fruition. It tells the story of Fergus O’Brien, grandfather of Joe, who left Ireland for America during the potato famine of the 1840s, passing briefly through Montreal. A tightly focused story proceeds with brief, punchy sentences, poetic language, snappy dialogue; an effective blend of intellect and emotion. A picaresque tale replete with the nail-biting swings of fortune and a high gore factor, it reads like a miniseries in waiting, at least compared to The O’Briens, an epic story best suited to the novel form.

Epic. Episodic. These words are generally bad news in the film industry, where Peter Behrens toiled for fifteen years, during an interlude between the publication of his short-story collection Night Driving (1987) and The Law of Dreams (2005). Learning this biographical detail after reading both books, I was tempted to speculate as to where that experience of storytelling had influenced his writing, and where it had not. His style is consummately visual, a series of scenes, as if the omnipo- tent author is holding a camera that can travel into people’s heads. By and large, he resists Hollywood conventions in The O’Briens; at least the story is epic enough to feel potentially true, and not just filmic.

Meeting Behrens this summer during his brief visit to Montreal for the Canadian Association of Irish Studies conference at Concordia University provided further insight into at least one reason why the novel feels true: he lifted huge chunks of detail from his own family history, using both the first and last names of family members, telling some secrets, spinning some lies.

Born and educated in Montreal, Behrens left as a teenager to work as a cowhand in Alberta, before settling in California. With his wife and their four-year old son, he now divides his time between a small town in Maine and small-town Texas. Keeping Montreal at a distance allows him to re-imagine the past with a certain amount of freedom, to fill in the gaps noticed by his youthful, observant self.

“In my grandfather’s generation, the famine was always the unspoken presence,” he said. “Our family culture was shaped by the famine experience. I remember driving by the Black Rock with my grandfather. He seemed to have a visceral reaction to the memento of suffering. That and his own travails may explain the tendency of silence in our family. There are things you just don’t talk about.”

Though personal history provided material, he was not constricted by truth, cutting and amending the facts where necessary.

“Genealogy bores me,” he says. “Family history is my thing. I guess it’s my way of staking a claim.” His next novel will draw on the paternal side of family history, the story of his father Herman Behrens who married an Irish woman. A tale no less riveting than Joe O’Brien’s.mRb

0 Comments