After winning several prestigious awards in its original French, Catherine Leroux’s second novel, The Party Wall, expertly translated into English by Lazer Lederhendler, has been shortlisted for this year’s Giller Prize and for a Governor General’s Literary Award for translation. And deservedly so. The novel unfolds in a series of intimately interrelated stories about unusual family relationships, intriguing the reader with original plot twists while remaining squarely focused on the lives and loves of its characters. The result is an intoxicating blend of the familiar and the uncanny, brilliantly executed.

The Party Wall is an unconventional narrative in both structure and style. The novel is composed of thirteen distinct sections of varying lengths that tell the stories of four families, each dealing with significant changes and revelations. The novel begins quietly, with a glimpse of two sisters taking a walk through their neighbourhood in Savannah, Georgia, before a life-changing accident. After a few pages we move to the next section, meeting a widowed photographer living on the Acadian Peninsula of New Brunswick and her wayward son, both coming to terms with the surprising results of a medical examination. Next we meet the young prime minister of a dystopian near-future Canada and his wife, whose relationship is revealed to be more complicated than it seems. And finally we are introduced to a San Francisco police officer and his sister, a former Olympic runner, whose family ties are tested in the aftermath of their mother’s death.

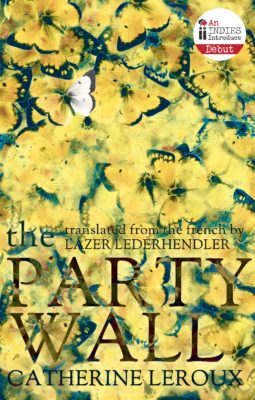

The Party Wall

Catherine Leroux

Translated by Lazer Lederhendler

Biblioasis

$19.95

paper

248pp

9781771960762

The Party Wall has the narrative force of a Hollywood film, while also offering richly executed portraits of the characters’ interior lives. The complications of biology haunt much of the novel and the unique bonds of siblingship underpin much of its drama. The individual plots are full of incident and constantly in motion, always developing in surprising ways that throw characters off kilter. While some of the characters are more fully realized than others, each becomes fascinating as they experience moments of heightened tension, including public scandals and personal health crises. Leroux shows each of the men and women in The Party Wall to be intimately human, even as they become unmoored and uncertain of their own identities.

The Party Wall is an intensely readable novel and its ingenious structure makes it far more than the sum of its parts. In Lederhendler’s English, Leroux’s style is an eloquent, lyrical realism and the novel is written in accessible and enjoyable prose with occasional stylistic flourishes. Focusing on characters from disparate times and places, Leroux puts forth a deeply humanistic message, one which suggests that bloodline need not be the sole determinant of one’s life. The Party Wall celebrates the many ways there are to be a family, even if those relationships are sometimes fraught.

0 Comments