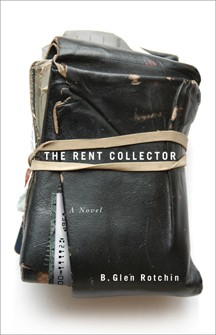

The Rent Collector

B. Glen Rotchin

Vehicule Press

$19.95

paper

228pp

1-55065-195-1

This story centres on Gershon, an Orthdox Jew and rent collector at his father’s building, 99 Chabanel. The goings-on in this building provide seemingly realistic insight into the world of the garment industry, and link well to the history of Montreal, to political issues in Quebec, and especially to Orthodox Jewish traditions and beliefs. The issues Gershon faces, meanwhile, are well-developed and complex, and include family obligations, dealings with conniving tenants, and attitudes on Israel.

The linchpin central to Gershon’s handling of these issues, and to his complete understanding of the world, is religion. The analogies he perceives as a result of his religious outlook, however, are sometimes more than a bit of a stretch. For example: “An observation suddenly struck him. There were similarities between the [Hell’s Angels] and the Orthodox Jews…[they] wore uniforms and wore long beards and so did religious Jews.” Similarly, he compares strippers to Orthodox Jews, Quebec Hydro to God, his building’s plumbing to the Dead Sea, an electrical bill to the Temple of Jerusalem, and owner’s manuals for cell phones to the Torah, which he sees as a manual to the world.

The problem with these comparisons is not that the character’s perception of them is borderline ridiculous. Most readers, I think, could find a religious character to be convincing, compelling, and fascinating to get to know. The problem is that the narrator, too, seems fundamentally religious, describing direct involvement of God in earthly matters without critical separation. Seemingly out of nowhere appear pronunciations like “The survival of Judaism was at stake,” or “The light of Judaism is fading with each subsequent generation,” while the story’s overall tone is moralistic. The narrator also tends to use terms that most non-Jewish readers won’t understand. (More than once I had to ask my Jewish partner what words meant, and he then often had to ask his grandmother.)

While objectivity in literature is inherently impossible—writers write because they have something to say—subtle subjectivity is the art of the craft. Guidance through a story inspires the reader to willingly re-examine his or her own understanding of the world, and perhaps learn something new. Didactic narration, however, invokes distrust and even a sense of betrayal, by leaving no room for the reader’s own interpretation.

One problem that arises from overtly subjective narration is that the whole work loses credibility. And this means that even otherwise believable characters tend to feel like a thinly-veiled attempt of the author to sidestep accountability when treading dangerous ground. Since the narrator states that for the Jewish community, “Remaining distinct meant remaining alive,” the characters can no longer get away with certain statements. When one character wonders if Jewish children are inherently altered by having Filipina nannies, or another sees a “plain” correlation between dress sales (and thus Jewish economic success) and the Cold War, or when Gershon dreams of “Arab boys pissing down on praying Jews from the top of the Wall where it met the Temple Mount,” these statements take on the colour of political motivation.

Similarly, Gershon’s infatuation with a young female bookkeeper (and leather clothing model) is suddenly particularly troublesome. He feels he may have glimpsed her “inner light” as he passes her in the hallway, just as “Moses chanced upon the light of God in the form of a burning bush at the foot of a desert mountain,” and even perceives a divine message in her name. Again, what is disturbing is not the personal weakness of Gershon as a character, but rather the narrator’s own apparent acceptance of the divine origins of this infatuation as well.

From the first pages of The Rent Collector, I wondered for whom this work is intended—the general public, or Orthodox Jews who might discuss it at kollel (evening study assembly). If it is not a religious exemplary text, then I hope it’s precisely the opposite, and that the religious narration is an intentional part of the design, a conscious emphasis on the all-pervasiveness of religion in the world of Orthodox Judaism, and not just a direct consequence of the author’s own beliefs. I hope that the irony is so deep that it was lost on me. mRb

0 Comments