Few figures are as stirring – and heroic – as a servant, walking a dangerous but noble path, abandoned by the very people who called him to it. We may not be capable of such idealism, but it reminds us of what faithfulness looks like. And the tragedies that usually accompany such missions show us true sacrifice and heroism.

In this case, the master who first called Claude Lacaille was the so-called Good Pope, John XXIII, in the 1960s. The path Lacaille took as this Pope’s servant, from 1965 to 1986, was to follow the Second Vatican Council’s directive to renew the church by reaching out to the poor and powerless in solidarity with Jesus (who was, as Lacaille reminds us, also murdered by soldiers). As the author recalls with some bitterness, the popes who followed John XXIII quickly tried to reverse his reforms. After the Council, the Church once again “allied itself with imperial power,” cozying up to tyrants. Lacaille isn’t afraid to name names, which may explain the fact that this book was not published by an official Vatican publisher. But like that of so many other children of Vatican II, Lacaille’s faith, having been radicalized, could not be extinguished. A true missionary, he writes, must “live among the impoverished and … support them in their struggles.” The book is full of similar pronouncements.

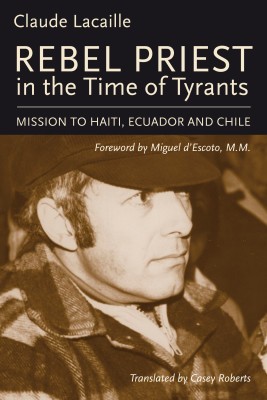

Rebel Priest in the Time of Tyrants

Mission to Haiti, Ecuador and Chile

Claude Lacaille

Translated by Casey Roberts

Baraka Books

$24.95

paper

232pp

9781771860390

Through it all, including his own brushes with danger, Lacaille tells his story. As a child in Trois-Rivières, he wanted to be a missionary. But he chafed at what he describes as the isolating, “infantilized” life of the seminary. His real education came in his first posting, the slums of Haiti: “this extraordinary people … made me the man I’ve become.” It’s telling how the author later enjoyed community life in Chile among young and old, women and men, “simple, full of sharing and brotherhood.” Lacaille’s true professors were Latin America’s revolutionary Christians. Here he found his home. At the end of the book, the author seems a bit lost back in Quebec.

The writing is simple, the translation by Casey Roberts sometimes overly colloquial. Even as a non-Catholic, I was only rarely lost by the vocabulary. The characters are compelling: worker priests, angry old men raising their fists at dictators, silent mothers protesting “the disappeared” while babies nuzzle their breasts, radicalized youth, twitchy carabineros (armed police), death squads, martyrs, torturers, and Bishops caught between the poor who occupy their churches and the dictators who sit at the front during official masses. Lacaille’s autobiography has all the ingredients of great fiction, which makes it more astonishing as truth.

The naiveté and audacity of statements such as “Our project would be to help our neighbourhood get back on its feet, to defeat terror and to get organized to fight oppression” would be laughable were there not evidence that Lacaille and the other little “red priests” (so named for their emphasis on social justice) in their own small way actually helped do all that. It helps that Lacaille is humble, a humility that clearly goes hand in hand with his love of the people.

A “Good Pope” stands at the beginning of Lacaille’s story. One wonders if it would have been told had there not also been a “good pope” – Pope Francis, a friend of liberation theology and advocate of justice – to bless and give hope to the end. mRb

0 Comments