“Tragedy can result from the most mundane detail in life,” a dramatist remarks about his own tale, in one of the nine stories in Montreal-based Xue Yiwei’s Shenzheners. One can easily imagine Xue making the same comment about his short fiction collection, originally written in Mandarin Chinese, and his first to be published in English. With a simple, elegant translation by Darryl Sterk, each story is titled after a character who lives a quiet, hidden suffering, an interior tragedy only barely visible to others. In “The Country Girl,” the protagonist endures a difficult marriage and unexpectedly confides it all to a stranger on the train. She ends up falling in love with him – the first Asian

she has ever spoken to – only for this romance to fail as well. “The Dramatist” retires from writing, cursed by the ultimate theatrical tragedy, as he is torn between the two women he loves. And “The Prodigy,” a piano wunderkind known to all in his city, cannot bear to tell his parents why he will not accept a prestigious prize, and so instead hides in the basement until the award ceremony is over.

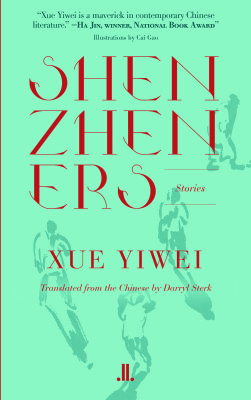

Shenzheners

Xue Yiwei

Translated by Darryl Sterk

Linda Leith Publishing

$18.95

paper

210pp

9781988130033

With this setting, a city of migrants from all over China, Shenzheners is rich in the metaphors common to migrant living. Xue’s curious eye observes the many layers of belonging that characterize migrant identity, and lends itself to depictions of the complex, felt experience of a range of identities – Chinese, Cantonese, Canadian, but also rural and urban, perhaps the strongest identity rift within China. His characters, having multiple identities, may spring from Xue’s

own experience as a Hunan-raised, Guangdong-educated transplant to Montreal. He deftly moves between the worlds described in Shenzheners – of women, men, children, of different social classes and Chinese regions. One gets the sense that Xue himself, belonging to many places, may feel an appartenance to several places at once, and in equal measure, no place at all – a reality for many migrants.

There is, too, a real attempt to capture the interior life of the nine protagonists – an homage, possibly, to James Joyce, to whom the book is dedicated, and whose Dubliners inspired this collection’s title. Xue’s characters wrestle with difficult – and often bad – decisions, and then try to drag themselves out of the wreckage. In “The Physics Teacher,” a young woman feels an affection for her student, an aspiring poet who elevates her out of a teaching slump. As her emotions veer towards romantic infatuation, havoc ensues, leading the poet to abandon his artistic dreams and to choose a life of “rationality” and “science” instead. The big sister in “The Two Sisters,” who was so keen on finding a reliable husband, ends up avenging her husband’s infidelity by sleeping with all kinds of men in his business network, only to contract a disease that destroys her.

Shenzheners is full of quietly devastating moments played out through the unsaid but deeply felt, not unlike the emotional landscapes portrayed in Ha Jin’s novel A Free Life, or Wong Kar-Wai’s film In the Mood for Love. Though oftentimes dark, Xue’s world is truthful, and manages to capture the strange poetry of life’s awkwardness. mRb

0 Comments