Between 1920 and 1940, an estimated three thousand orphans were left in the care of nuns at the Hôpital de la Miséricorde in Montreal’s east end. This is where Heather O’Neill’s latest novel, The Lonely Hearts Hotel, begins: in the grim, grey orphanage, where even the most fragile babies are seen as little more than evidence of sin. Two such children – Pierrot, a presumed stillborn who miraculously comes back to life, and Rose, named for the marks that bloom on her cheeks when she’s found abandoned in the snow – manage to thrive in the orphanage, entertaining the other children and turning contemptuous remarks into words of affection.

Together the two children are a rather fabulous act. So good, in fact, that they perform at the homes of wealthy families around the city to the financial benefit of the institution. It’s a fairly decent existence, one that allows the children to dream of a future when they can take their show on the road. But their dream is not to be. Cruelly separated, the two live out their teenage years getting into petty crime and heroin (him) and transitioning from nanny to mistress (her).

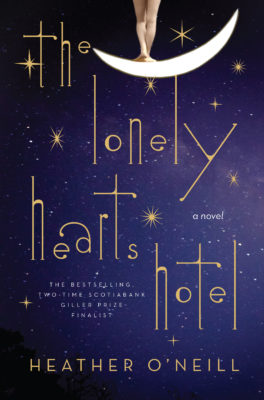

The Lonely Hearts Hotel

Heather O'Neill

HarperCollins

$32.99

cloth

400pp

9781443435864

Those stars, however, are the siren call of the underworld. The seedy underbelly of the city is controlled by gangsters, and Rose quickly starts scheming ways to join them. Following her touching reunion with Pierrot, the two sweethearts begin to plan their touring show. The Snowflake Icicle Extravaganza is a showcase for the city’s saddest, most absurd clowns. They ride out on bicycles, arrive naked in bathtubs, and drunkenly tightrope walk over the audience. O’Neill is known for her whimsy, and nothing is as whimsical as this – think proto–Cirque du Soleil.

That same playfulness runs throughout the novel and is most affecting when used as a coping mechanism, for instance, when we see Rose, the nanny, wandering the garden blindfolded, her charges following blindly along. This wonderful imagery continues with striking metaphors on almost every other page: “The orchids hung over the cast-iron gates like girls in just their petticoats yelling at the postman for a letter.” Such imagery is one of her strengths, but O’Neill is at her most confident describing the lives of the down-and-out: their shabby underwear, threadbare suits, and decrepit one-room apartments. The beautiful contrasted with the vulgar creates a world that feels more make-believe than real – a world in soft focus.

As Rose’s commitment to the Extravaganza grows, Pierrot recedes. There’s little room for a dreamy, kind-hearted junkie when you’re on a mission to control your future. Rose and Pierrot are on course to rule Montreal’s underworld, but where Rose is willing to do anything to secure her place, Pierrot is uninterested in becoming a gangster. The choice both characters face is simple and universal: do you choose to create your own future or continue to be controlled by your past?

By placing this question at the centre of her story, O’Neill challenges the overall tone of the novel, positioning Rose as a woman battling for equality, rather than a victim of circumstance. While The Lonely Hearts Hotel remains a novel about two lovable eccentrics, Rose’s drive and feminist spirit balance out the novel’s fantastical aspects; the result is both more genuine and more meaningful.

0 Comments