In Suzanne, first published in French as La femme qui fuit (the woman who flees), Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette’s grandmother takes her place in a long roster of literary missing persons – from April Raintree to Amy, the Gone Girl – who form, through absence, the driving force of a novel. But rather than build her narrative around a grandmother-shaped hole, Barbeau-Lavalette has chosen to construct Suzanne Meloche in fiction. Working from accounts of friends and family, the reports of a private detective, and a writer’s compulsion to imagine other lives, Barbeau-Lavalette draws a portrait of a complex woman who lived on the cutting edge of her era. Her prose is spare, direct, sometimes curt. The use of the second person for Suzanne’s narrative voice is a bold move that a less skilled writer might not be able to pull off, but the strong, clipped sentences seem fitting for a woman who pushed boundaries and broke with expectations.

After a prologue where Barbeau-Lavalette sets up Suzanne’s absence in her mother’s and her own life, the story opens in 1930s Ottawa, where Suzanne is growing up in poverty, along with everyone else. She’s an intense, independent girl – a girl with mud in her underwear; a girl who picks at her fingers until they bleed; a girl who, wanting to leave an impression during her first confession, licks the lattice between herself and the priest. Young Suzanne fixates on reports of Montreal sprinter Hilda Strike, and by the time she’s nineteen is on her way to live in Quebec, “where the women run fast.”

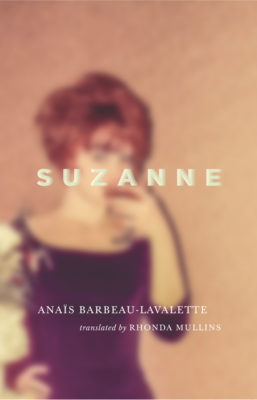

Suzanne

Ana's Barbeau-Lavalette

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

Coach House Books

$20.95

paper

224pp

9781552453476

Although they were at best dismissed and at worst censured (Le Refus global cost Borduas his job), the Automatistes were the vanguard of a social movement that ushered in a new era for Quebec, and Barbeau-Lavalette’s fictionalized account is fascinating to read, especially in the context of contemporary Quebec social movements like the printemps érable. But though the Automatistes attempt to shake off the yokes of capitalism and religion to embrace “total freedom,” there remain certain vestiges of patriarchy. For example, while her husband Marcel Barbeau takes extended trips to show his paintings, Suzanne must stay home with their children. Her struggle to balance family life with her own artistic awakening leads her to a choice that is not unheard of in itself – but for a woman, and at the time, it’s a shocking one. This novel is perhaps Barbeau-Lavalette’s attempt to understand that choice, to explore the dynamics of family obligation, feminism, art, and individuality that shaped Suzanne’s life, and thus the lives of her descendants.

I finished reading Suzanne on Mother’s Day, the significance of which was not lost on me. On a holiday that celebrates motherhood but also flattens its complications into tulip emojis and sales on aprons, it seemed appropriate to read an unflinching portrait of a woman not especially doting or nurturing, who was unable or unwilling to meet the demands of both family and art. And to consider the context in which she chose to leave her family, and to wonder how much that context has changed. Suzanne is a moving story of a woman constrained by circumstance and freed by an act of will – whatever you make of it – and it captures an exhilarating period of Quebec history, and of a singular experience of that time. mRb

Even the voice of the review is a companion to the novel.