Armand Gamache is now Chief Superintendent of the Sûreté du Québec. He’s in charge, the boss of the whole Sûreté, but to deal with the great challenges that await him, he surrounded himself with his usual, trusted team: Jean-Guy Beauvoir is his second-in-command, Isabelle Lacoste is head of the Homicide department. A new addition to the people he trusts is Madeleine Toussaint, the first woman and Haitian to head the Serious Crimes department. After cleaning out the corruption that had taken over the Sûreté, he now needs to stop, or at least put a serious dent, in the province’s crime levels. That, and solve another murder in Three Pines, the small Eastern Township town that doesn’t appear on any map and that nobody knows exists until they happen to fall upon it.

The day after Halloween, a figure dressed in a black cloak, wearing a black mask, shows up in Three Pines. Picture the black, ominous figure in Amadeus, but without a tricorne. First, it’s present at the yearly Halloween party, then it stands, stock-still, in the village green. The figure, it turns out, is a cobrador – a moral debt collector that originated in medieval Spain, a conscience. Unnerving as it is, the cobrador doesn’t actually break any laws, and Gamache can’t do anything until, a few days later, the figure is no longer there.

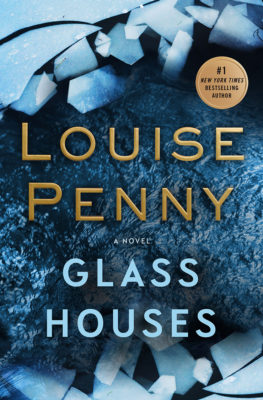

Glass Houses

Louise Penny

Minotaur Books

$33.99

cloth

392pp

9781250066190

The interesting thing about many of the Gamache novels is that, unlike other crime novels where the sole focus is the murder and, sometimes, the personal life of the inspector, they also encompass a bigger picture. Yes, Gamache has to solve a murder, but he’s also a leader in the Sûreté and he has bigger fish to fry. Ever since the disastrous shootout in the sixth book, Bury Your Dead (2010), the series has been more than a simple “who-done-it.” After uncovering corruption within the force, weeding out the bad elements, and training a new generation of cops, Gamache now tries to win the war on drugs.

Penny has always substantially developed the characters that surround the main inspectors, giving them dreams, projects, a life outside of crime and murder. In Glass Houses, she even succeeds in turning Death into a looming, upsetting character. This presence is hardly surprising, since Penny wrote the book as her husband was dying and after he died. Very early in the book, death is not simply the result of murder, but a presence that doesn’t loosen its grip on readers, even after finishing the book. Its black presence is part of life. mRb

0 Comments