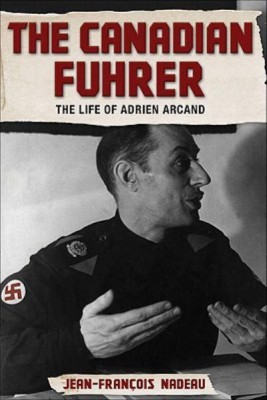

The Canadian Fuhrer

The Life of Adrien Arcand

Jean-François Nadeau

Lorimer

$35.00

Cloth

9781552779040

The Canadian Führer explores the life and impact of a virulent anti-Semite, Adrien Arcand (1899–1967). Now largely forgotten, Arcand achieved notoriety during the 1930s as the charismatic head of a series of far-right organizations and newspapers.

Jean-François Nadeau gives a highly readable portrait of a malevolent and shadowy figure, while also providing a well-informed outline of the right-wing Catholic movements that once flourished in Quebec. Although Arcand’s own movement was small, Nadeau reveals that he received support from key establishment figures over several decades. Nadeau also shows that Arcand’s life intertwined with those of a number of famous figures, including the artist Jean-Paul Riopelle (who admired him in his youth), the French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline (who attended one of his fascist meetings in 1938), and future Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau (who, as a law student, criticized his incarceration under the War Measures Act, a statute later deployed by Trudeau himself).

Depression-era Quebec was rife with groups that flirted with fascism and anti-Semitism. Arcand’s movement went beyond the point of flirtation by ostentatiously embracing the symbols, rhetoric, and style of Nazi Germany. He crammed his newspapers and pamphlets with anti-Semitic articles and cartoons of the most poisonous sort (one cartoon, reprinted in this book, depicts a hook-nosed, bearded, and leering octopus encircling the globe with its monstrous tentacles). Furthermore, his disciples staged mini-versions of Hitler’s mass rallies and paraded in uniforms adorned with swastika armbands.

Arcand always viewed himself as a faithful, indeed fervent, Roman Catholic. He was both hurt and surprised when Church leaders reacted to his movement with hostility. He did get some support from a few clergymen on the ultra-right fringes of the Church, but mainstream Catholic authorities were wary of a man who so closely modelled his movement on a regime linked with neo-paganism and the persecution of Catholics.

Although a Francophone with his main base of support in Quebec, Arcand staunchly supported a united Canada, the British Empire, and the British monarch. At party meetings, members would raise their arms in fascist salutes and yell: “Long live the King!” Arcand’s preference for hereditary monarchy may have stemmed in part from his nostalgia for the Middle Ages. He felt revulsion for most modern ideas and currents of thought. The Enlightenment, liberalism, socialism, communism, and the theory of evolution were frequent targets of his polemics. His prime target, however, would always be the Jews, whom he loathed with rabid intensity. He took it as an unquestioned axiom that Jewish conspiracies were responsible for the world’s ills.

For a hate-filled monomaniac, Arcand could be surprisingly pragmatic, a theme explored at length in this book. For tactical reasons, Arcand often urged his supporters to vote for mainstream conservative parties such as the Union nationale, which returned the favour by giving him small sums of financial aid through much of his life.

In 1938, as war with Germany loomed, Arcand realized it might be prudent to keep some distance between his movement and Hitler’s regime. He began to curb his overt references to Nazism, but the subterfuge fooled no one. Arcand was incarcerated under the War Measures Act from 1940 to 1945. A pathological liar, he had so exaggerated the strength of his movement that authorities became genuinely alarmed. It didn’t help matters that he had conducted a vast correspondence with Nazi supporters and sympathisers overseas.

Arcand emerged unrepentant from his wartime imprisonment. He kept up and even increased his correspondence with anti-Semites across the globe. He helped launch the holocaust-denial industry and came to be treated as a mentor by Ernst Zündel and his ilk. Arcand remained a paranoid bigot to the end, all the while regarding himself as an upstanding Christian.

The arts editor at Le Devoir, Nadeau is also an accomplished historian. He is an expert on the right-wing thinkers and figures who were active in Quebec during the period covered by this book. Nadeau is thus able to contrast Arcand’s movement with the other, usually far less fanatical, right-wing groups that thrived in this province during Arcand’s lifetime. The breadth of Nadeau’s research is impressive: his extensive endnotes show evidence of long days spent in archives. Nadeau’s main text, however, is written in an engaging style. This book is of great worth to professional historians, but it will also appeal to a broad readership. mRb

I guess an objective book was too much to ask for, these authors think it’s their job to condemn instead of presenting the ‘facts, and letting the reader decide about the man.

I read this book which was given to me by my historian son. I new about Arcand although I was happy to read this book. However I was’nt enthused about the writing style of Nadeau which I thought too repetitive especially when he began a new paragraph or when he brought a new proposition. Last week I read an article in Le Devoir and I thought his writing style was good then.