Early in Leila Marshy’s novel The Philistine, the protagonist, Nadia, abruptly declines to board a return flight from Egypt to Canada and arranges instead for an open-ended ticket allowing her to stay indefinitely. What looks at first glance like a refusal to go home becomes far more ambiguous because of how the novel unsettles the categories of home and away, travelling and arriving, belonging and exile. Marshy deftly explores how moving between places always means moving between different versions of one’s self, including versions that may seem unrecognizable.

Nadia is the daughter of a Palestinian father and Canadian mother, born and raised in Montreal, but with her worldview and identity intensely interwoven with her Middle Eastern heritage. When her father abruptly returns to Egypt, leaving her and her mother behind, Nadia is left with gaping questions that she finally seeks to answer, five years later, by planning an impulsive trip to Cairo to seek him out. The initially short duration of the trip is extended because of two complicating factors: her father’s reticence to welcome her into his new life and the start of a love affair between Nadia and Manal, a young Egyptian woman with aspirations of studying art abroad. When Nadia decides not to board her flight, she is driven by multiple intersecting forms of desire: desire for Manal, desire for a deeper relationship with her father, and desire for an understanding of her own Palestinian identity. As she comes to understand during the time she spends in Egypt, “we are always travelling towards something … and it was more often than not the past.”

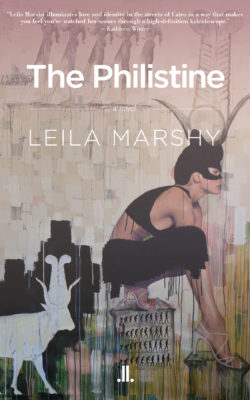

The Philistine

Leila Marshy

Linda Leith Publishing

$18.95

paper

320pp

9781988130705

Refreshingly, Nadia’s relationship with Manal blends seamlessly as one theme among many in a narrative focused on growth, exploration, and the navigation of identity. Nadia’s recognition that her sexuality is more fluid than she had previously understood reinforces that perhaps everything about her is likewise mutable. Marshy’s controlled prose underscores this complexity: “‘I guess I’ll stay in Cairo as long as it takes.’ Then [Nadia] added, realizing it could be anything: ‘Whatever it is.’” The beauty of The Philistine is the novel’s ability to recognize and celebrate journeying across places and into one’s self, even when the destination is perpetually shifting. mRb

0 Comments