From the first page of Jennifer Quist’s new novel, we know who the murderer is. “These events were not random and there is currently no threat to public safety,” a police spokesperson says in a prepared statement. Brett Finnemore, the victim’s murderous boyfriend, has been caught and charged, and is awaiting his day in court.

So now what do we do?

What do we do in a crime novel where there is no hard-boiled detective working the case? No tenacious cop playing cat-and-mouse with the killer, no small-town spinster shrewdly putting together clues? What do we do when we walk into the story after the thrill of the chase?

In The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner, we sit with the people left behind, the family of the murdered woman, as they struggle to find a way to live in the lengthy purgatory between the murderer’s arrest and his conviction.

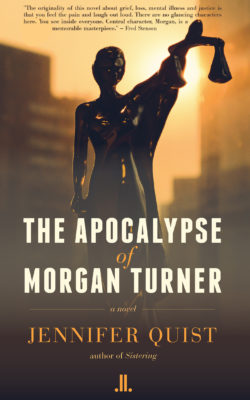

The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner

Jennifer Quist

Linda Leith Publishing

$18.95

paper

300pp

9781988130620

And then there is Morgan Turner, the victim’s younger sister and the title character of the book, who is poor and poorly educated, intensely private, and has no friends other than her brother. As the months between Brett Finnemore’s arrest and the start of his trial drag on past a year, Morgan struggles to make some sense of what happened to her sister. She takes a job at the local abattoir, seeking “a proper horror movie—one with a storyline she can watch unfolding with a beginning, a middle, and someday maybe, an end.” She puzzles over whether exorcism and the devil and holy water are real and if so, what they look like. She becomes friends with a man whose schizophrenia makes it impossible for him to keep his life together – an interesting counterpoint to the fact that Brett Finnemore, the killer, is putting forward a defence of Not Criminally Responsible by reason of a mental disorder.

There is sensitivity and lyricism in Jennifer Quist’s writing. There are keen observations and scenes of exquisite compassion, particularly the ones that involve Morgan’s interactions with her unexpected new social circle of Korean-soap-opera-loving Chinese immigrants. There is grim humour, too. In the courtroom, Tod refers to the half of the gallery behind the prosecutor’s desk where they sit as “the bride’s side.” When Morgan’s anxious fingers wander to the bottom of the bench, she finds that “someone has left a wad of gum as a protest, sticking it to the court system the best way they could.”

Readers wanting a fast-paced whodunit should look elsewhere. The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner is for those seeking something graver and richer, more nuanced and thought-provoking, something with no easy ending, however the verdict comes back. They will leave it feeling, as Morgan did after finally seeing the inside of the abattoir, “like any new initiate, considering something that was much less and much more than expected, all at once.” mRb

0 Comments