Just like its namesake street, Abla Farhoud’s newly translated novel is populated with memorable characters from all walks of life. Young and old, settled and transient, the characters weave in and out of each other’s lives, inhabiting a modern, multicultural society that shares its neighbourhood with a thriving but insular community of Hasidic Jews. In brief, vivid chapters, Farhoud provides glimpses into the lives of the Montreal residents who inhabit Hutchison Street, which “does not separate Outremont from Mile End, as you might think; it brings them together.”

Each chapter in the novel focuses on a single character, offering a sympathetic and nuanced portrait of their individual fears, loves, and dreams. Many of Farhoud’s characters are friendly, open-minded, and successful people, but others suffer from mental or physical illness, addiction, or loneliness. The reader dips in and out of each character’s life, spending a few difficult days with the unhappy Martine Saint-Amant, who reads detective novels “to offset the crushing weight of her pain,” then flitting across the street to follow the easy-going Hershey Rozenfeld, who is proud to operate “the only kosher store in the neighbourhood where Jews and non-Jews congregated comfortably.” We share in the major triumphs and tragedies of each character’s life, learning what brought each of them to Hutchison Street and what made them stay.

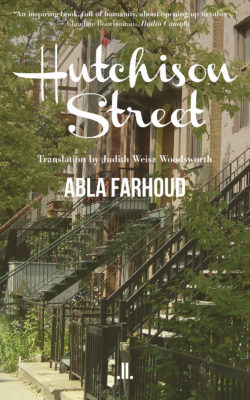

Hutchison Street

Abla Farhoud

Translated by Judith Weisz Woodsworth

Linda Leith

$18.95

paper

230pp

9781988130743

Dreams are “often how novels are born,” writes Farhoud, and Françoise starts this novel by “dreaming about the people on her street, especially the Hasidic people.” Realizing that her neighbourhood is “teeming with characters,” Françoise begins to write this book, penning chapters that portray the neighbours she sees every day. This leads to a pleasantly dizzying reading experience, with Françoise becoming a stand-in for Farhoud and detailing an intense writing process that surely echoes that of the author herself. This meta-construction is pushed to its limit when Jean-Hughes, Françoise’s publisher and long-time lover, wonders how Françoise “would depict him if he did become a character in her novel.” Serving as the book’s main plot, these extraordinary descriptions of Françoise’s writing process keep pace with the advancing novel, blurring the line between fiction and truth as our fictional author invents names for her fellow characters and produces the very book we are reading.

The other recurring character in Hutchison Street is Hinda Rochel, a Hasidic teenage girl whose diary entries document her struggle to fit in with her community’s strict religious laws. Like Françoise, Hinda Rochel loves education, reading, and writing, and she chafes against the limitations of the domestic space where she is expected to remain. When she says that she plans “to write a book one day,” her mother is dismissive, saying “when you have children, you won’t have time for anything else anymore.” Besides a battered copy of a Gabrielle Roy novel, Hinda Rochel’s only escape from her wearisome life is a slow-blooming friendship with Françoise.

Hinda Rochel’s hunger for stories and self-expression is echoed in the other chapters. Although a number of characters are isolated or estranged from their families, they find joy and solace in theatre, music, and books.

The first of Farhoud’s novels to be translated into English, Hutchison Street retains the cadence and flavour of a francophone novel. Farhoud writes convincingly from both an outsider’s and an insider’s viewpoint, celebrating the diversity and energy of the book’s Montreal neighbourhood: “That’s what makes Hutchison Street so unique, a street split between Mile End and Outremont. Between Yaveh, God, Allah … or none of the above.” mRb

0 Comments