Canada is rich in Indo-Canadian fiction writers: Rohinton Mistry, Ameen Merchant, and Padma Viswanathan spring to mind, among many others. Most of their work has, like Anita Rau Badami’s, either been set wholly in India (Hero’s Walk) or divided between India and Canada (Tamarind Mem, Can You Hear the Nightbird Call?). Now, however, we are seeing books whose characters are not only Canadian-born, but a generation or two removed from the supremely disruptive act of immigration. Tell It to the Trees, Badami’s new book, is one of those. From birth to death, its characters are people of a snowbound landscape.

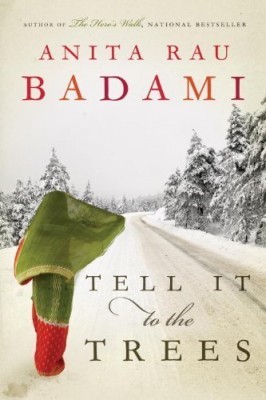

Tell It To The Trees

Anita Rau Badami

Knopf Canada

$32.00

Hardcover

336pp

978-0-676-97893-3

Varsha Dharma is the teenaged daughter of Canadian-born parents. Her family lives in the house that her mysterious immigrant grandfather Mr. J.K. Dharma built in the wilderness outside a small town in northern British Columbia. When Varsha’s mother dies, her father goes to India to get a new wife. Suman, the new bride, could not have imagined the cold and isolation awaiting her.

Varsha’s father is a violent autocrat whose patriarchal power deforms all of their lives; he uses Indian culture as a reference point to reinforce his control over the family, even though he had never been there before going to find a wife. As a result, Varsha and her little brother Hemant become secretive, plotters who constantly struggle to suppress the details of the violence they live with.

The plot turns around the arrival of Anu, who rents the cottage behind their house. The novel opens with her death by hypothermia; it is the quest to find out why she died that pulls the reader through the story. Yet the momentum of that plot device runs out partway. Badami’s style is didactic, explaining the obvious: the father is violent and the weather cold. She spends too long setting up the action instead of moving the story along. New information appears much too late.

This story is undermined by the weakness of its imagining – which will surprise anyone who has read Badami’s previous vivid tales. It feels as if it was meant to be a small family epic, starting with the tantalizing figure of Mr. J.K. Dharma, who moved so far from everything in search of silence. But we learn almost nothing more about him, and little else about the history of the family. We see that Akka, Varsha’s ailing grandmother who lives with the family, is more complex than she first appears, but we are never allowed to explore her past. And it is often hard to credit the explanations offered for the behaviour of the other characters. Anu’s shift from her intense Wall Street career to her tenancy in the back house is tough to swallow, and her death is equally hard to believe. The reader never comes to care for her, so her death, which ought to drive the plot, has little impact.

Varsha undergoes what would have been an interesting personality change if drawn with more finesse; instead, it comes across as one of those children-are-evil horror movies, but without the suspense. And the landscape, absolutely necessary to both the plot and the mood, is like a cardboard backdrop. We are told the snow is up to the eaves, yet we rarely feel it blow into our faces, hear it crunch, or see the glare that makes one squint. The anticlimactic ending completes the reader’s feeling that the book is built backwards in an effort to shore up a weak plot. If Anu’s death were not announced at the beginning, perhaps Badami would have been forced to build more powerfully toward it. Instead, this potentially gripping Indo-Canadian Gothic is deflated and disappointing. mRb

0 Comments