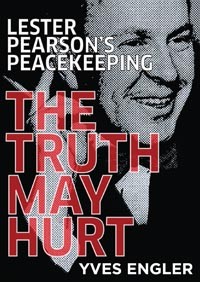

Lester Pearson’s Peacekeeping

The Truth May Hurt

Yves Engler

Fernwood Publishing

$15.95

paper

160pp

9781552665107

The book’s foreword is written by Noam Chomsky, and the book as a whole resembles Chomsky’s well-known political works. Like Chomsky, Engler challenges conventional opinion by digging up facts that are often ignored or downplayed in mainstream journalism and scholarship. Pearson has sometimes been depicted as a war-hating anti-imperialist, but Engler convincingly portrays him as a man who built his career by promoting the economic and military interests of the major western powers.

Unfortunately, Engler shares Chomsky’s weaknesses as well as his strengths. Like Chomsky, he cites the most disturbing facts he can find while seldom placing those facts in broader context – unless doing so would further cast his target in an unflattering light. Not surprisingly, those at the receiving end of such treatment end up looking repulsive.

Although the extensive endnotes give this book an air of scholarly objectivity, it is a catalogue of one-sided criticisms against Pearson rather than a work of fair-minded scholarship. There can be great merit in books that promote contrarian political views, but the best contrarian works make an effort to address potential objections to their arguments. Engler takes only the most perfunctory steps in this direction.

Engler depicts Pearson as motivated by Cold War fanaticism. Pearson’s defenders would surely respond that his efforts to contain the spread of communism were prompted by a legitimate concern that Marxist-Leninist states posed grave threats to human flourishing and liberty. Engler barely deigns to address such concerns. He responds to the idea that Stalin’s Soviet Union posed a serious threat in only a few quick paragraphs, and he repeatedly treats Pearson’s expressions of worry about communism as evidence of paranoia.

In fairness to Engler, this book is not meant to be an exhaustive work of scholarship. He describes the book in terms of evidence gathered for an imagined truth and reconciliation commission on Canada’s foreign policy. Alas, in presenting evidence for this imaginary commission, Engler tries to critique Pearson’s vast foreign policy career in too brief a space, with predictable results. Engler discusses Pearson in relation to dozens of international events: World Wars I and II, the creation of Israel, the decolonization of Africa and Asia, the Suez Crisis, the CIA-sponsored coups in Iran and Guatemala, the Korean and Vietnam Wars … the list goes on (it includes some events in which Pearson’s involvement was trivial).

In citing so many events in such a short book, Engler presents them in highly simplified form. He sticks to a consistent narrative in which the USA – or another western power or ally – promoted brutal oppression with the assistance or encouragement of the unscrupulous Pearson. Engler has no interest in discussing mitigating factors, gruelling choices between unpalatable alternatives, or similar considerations; he marshals historical facts almost solely as ammunition for moral blame. Such an approach to history has its fans, and these fans will greet Engler’s book with enthusiasm. Readers who appreciate nuance will be less impressed.

0 Comments