It is 1922, and your native city has been on fire for nine days. You have lost everything, and are living as a refugee in a new city where you know nobody. What do you do?

In The Goodtime Girl, Tess Fragoulis’ second novel, this question is an important one. Kivelli Fotiathi is a pampered young woman living with her family in Smyrna. She dreams of marrying an “American naval officer” and of moving to Paris, London, or New York, but in the meantime, her day-to-day life doesn’t sound too bad. She goes to balls, strolls along the streets with her friends, reads Colette, sneaks out at night to go on clandestine dates. Yet this luxurious world is shattered when Smyrna is attacked and burned in the Greco-Turkish war. Kivelli is lucky enough to escape on a boat to Piraeus, but then has to deal with the trauma of surviving this horrific event.

Tess Fragoulis, on the other hand, was born in Crete, now lives in Montreal, and teaches at Concordia. In writing The Goodtime Girl, she had to deal with the difficulty of capturing Kivelli’s traumatic experience in fiction, and she came up with an interesting trick to do it. We do not read about the Great Fire of Smyrna until more than two thirds into the book. Before that, we only get hints of what happened between Kivelli’s carefree days in Smyrna and her life in a brothel in Piraeus. We hear about “the Catastrophe” and “the thunder of collapsing buildings,” and while the Great Fire of Smyrna will be familiar to many of us from Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex, we are still propelled forward in the story by our desire to know what Kivelli saw that has left her scarred.

You might think that keeping this scene from readers for so long would alienate them from the character, given that Kivelli’s life was changed so profoundly by the fire. But Fragoulis’ trick actually allows us even more access to Kivelli’s thoughts; it is as if the book itself were enacting her attempts to forget.

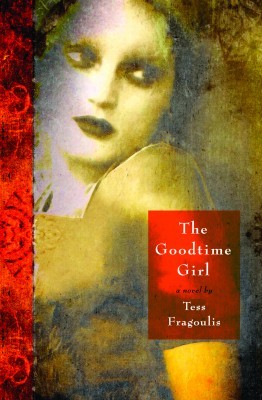

The Goodtime Girl

Tess Fragoulis

Cormorant Books

$21.00

paper

322pp

9781897151730

Fragoulis’ Greece is like a nineteenth-century painter’s image of the Orient: lush, colourful, not quite real. Her similes and metaphors can be over-the-top – Kivelli is “a Smyrnean rose with a scent as fresh and intoxicating as an orchard at sunset,” Kyria Effie’s words march out “like prisoners of war in the hinterlands heading to their doom” – and while these ornaments detract from the scenes Fragoulis has created, they do not make the story any less captivating. Kivelli is a young woman who survives against all odds, leaving her charmed past behind to make it big in a man’s world of brothels and brawls, ouzo and hashish and rebetika. You aren’t likely to forget her journey. mRb

0 Comments