In classical mythology, Persephone is forcefully separated from her mother and taken to the underworld. She is eventually able to return, but the reunion is incomplete: Persephone must forever spend a portion of time hidden away, moving through a cycle of appearance and disappearance tied to the seasons. Through both indirect and direct reference, this myth infuses Ariela Freedman’s novel A Joy to Be Hidden, where secrets, loss, and separated family members interweave through multiple plot lines. The novel’s epigraph quotes D. W. Winnicott’s caution that “It is a joy to be hidden, and a disaster not to be found,” but the allusion suggests a grimmer inevitability: that what has been hidden can, at best, only ever be partially recovered.

The novel is narrated retrospectively by Alice, who recalls with both fondness and exasperation the experience of being a graduate student in New York City in the 1990s, a time when New York “was already beginning to lose its edge” and academia revolved around narratives of literary theory that “celebrated the end of truth and the abyss of meaning.” While readers get some window into Alice’s day-to-day life, punctuated by attending guest lectures delivered by Derrida and ill-advised trysts with classmates, the novel’s action is spurred by two chance encounters. After Alice’s paternal grandmother Helen dies, she comes across a selection of items that suggest the possibility of a complicated family history and encourage her to begin investigating. Almost simultaneously, Alice strikes up a friendship with Persephone, an eleven-year-old girl living in a neighbouring apartment. Persephone’s precocious nature, and the freedom (bordering on neglect) allotted to her by her feckless mother Fiona, draws Alice into a family drama unfolding in the present, as she delves into trying to understand what has shaped her own family’s past.

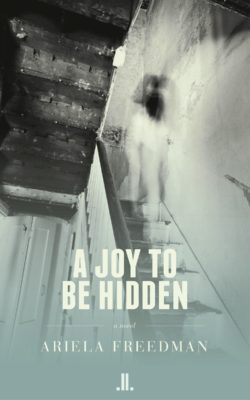

A Joy to Be Hidden

Ariela Freedman

Linda Leith Publishing

$19.95

paper

276pp

9781773900087

Alice’s capacity to see herself and her own moment in history with such clarity arises from her connection to a young girl, and to a much older community of women, her grandmother’s generation of Holocaust survivors. Helen and Bella are each given portions of the novel to speak in their own voices, with the insertion of journals and letters telling their stories. These portions, nonetheless, feel something like fragments, incomplete at best and tantalizing in what they allude to without ever fully revealing. Alice remarks of her grandmother early in the novel that Helen “had always been still and silent, but she was never serene, she was just hidden.” The truth of this statement only becomes fully apparent when the novel ends with a suddenness mirroring an unexpected death. Readers, like Alice, may mourn the lost opportunity to hear more of the story, to scratch deeper below the surface of something that was beginning to be revealed. What gives Freedman’s novel such a haunting power is the willingness to withhold a fixed and complete narrative, and allow finding to exist as an imperfect triumph. mRb

0 Comments