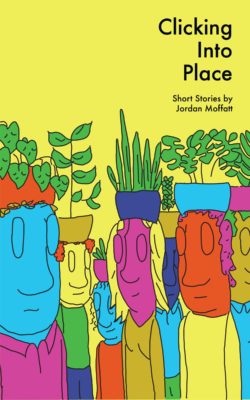

Clicking into Place, by writer and improviser Jordan Moffatt, is a different kind of book – it’s a Bad Book, the first fiction title from the micro-press founded by Fawn Parker and Thomas Molander in 2018. The press’s mission is to “broaden the definition of ‘CanLit,’” and Moffatt’s flash fiction collection fits the bill – it’s unlike any CanLit I’ve read in recent memory – but not in the ways I expected.

For one, it’s not an overly political book. It is, on the other hand, a humorous one. In literature, and especially Canadian literature, humour is grossly undervalued – to say nothing of the skill it takes for an author to use humour effectively in writing. Moffat mostly does this well, using absurdity, chatty prose, and uncomplicated characters to make for a breezy read.

Most of the stories in Clicking into Place operate on an offbeat premise that is spelled out in the title, as in “I Wear Plants for Hats,” “My Landlord is a Spider,” or “This Beach is Closed Due to Sand Mutants.” Where ideas are concerned, the author’s experience as an improviser feels apropos. As one of his characters learns in “I’m a Super-Intelligent Bonobo,” saying “yes” to new ideas is the first rule of improv, and Moffatt seems willing to run with almost any idea at all.

Clicking into Place

Jordan Moffatt

Bad Books

$12.00

paper

60pp

9781999530204

“Everything Around Me Keeps Turning Into Rocks” is also memorable. In it, a first-person narrator finds himself late for a date with a friend as the fixtures of his world are transformed, in phases, into numerous heaps of stones. In the same vein as Robert Coover’s surrealist “Going for a Beer,” this forward-lurching narrative is delightfully disorienting; a thing is what it is until it suddenly isn’t. When the narrator orders an espresso, for instance, and is served rocks, he tries to “complain to the barista but the barista was just a pile of rocks and the table I’d saved was also a pile of rocks and that’s when I realized I wasn’t at the café at all…” Et cetera.

Most of Moffatt’s characters have millennial sensibilities: they dream of Universal Basic Income, read about lifehacks on the internet, and have names like Dakota and Zandon. In contrast, their emotional register seems on par with that of characters out of a1950s sitcom. There is a cheery wholesomeness to the lessons they learn, such as in “My Great Idea,” where the protagonist feels down after a friend rejects his idea and finds solace in his father’s unconditional support. The story ends with father and son saying “I love you” to each other before they go to bed, and the triteness of the moment feels both deliberate and comical.

Clicking into Place is not a hefty book, neither literally – it’s just over fifty pages long – nor figuratively. Readers looking for a hard-hitting message may not find one, but that seems to be the point. In our increasingly fraught times, Moffatt’s stories offer a brief but pleasant escape. mRb

0 Comments