Grégoire Courtois’s novel The Laws of the Skies conducts a visceral experiment with both narrative and human nature. It removes all prospect of hope from the outset, then creates a spectacle of waiting for forewarned deaths to occur, rather than generating suspense about whether or not they will.

A group of twelve six-year-olds and three adult chaperones head into the woods for an overnight camping trip; the jacket blurb states starkly that “None of them make it out alive.” By the end of the first page, the narrator has affirmed in equally bald terms that “The children were on their way. They would never return.”

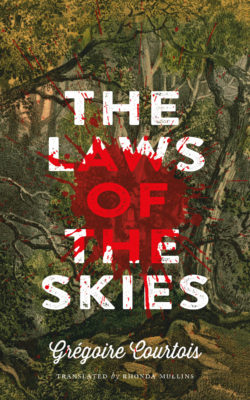

The Laws of the Skies

Grégoire Courtois

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

Coach House Books

$19.95

paper

148pp

9781552453872

The experience of hope is calibrated by the construction of a world where the faint possibility of justice still lingers. The deaths depicted in the novel alternate between the slaughter of innocence and moments of poetic justice where a death seems to be delivered as a form of punishment to a predator. Either way, there is an element of spectacle and shock to many of the deaths: rarely are they quick, and rarely are readers spared a confrontation with their graphic and meticulous representation. The longest and most explicit death scene is doled out to the character who commits most of the novel’s atrocities. The narrator takes pains to specify that “we will try to be as precise as possible, so that you can more clearly picture the scene that follows, so that you can fully experience what it would mean to be immobilized, tied up, powerless, suffering.”

Just before violence erupts, the teacher supervising the children recounts a fable with a grim and bloody climax, giving rise to the novel’s title through an allusion to natural laws being enforced. The spectre of nature hovers over the entire text: is this what we become when left unchecked? Is innocence simply the obverse of brutality? The adult characters are shown with varying degrees of moral ambiguity, but with only one exception, the children are kind, helpful, and capable of clinging to a basic form of community amidst chaos. That the children both live and die in some suspended state prior to full knowledge of good and evil seems to make little difference in the end. When the narrator explains that “a child doesn’t die like you, an adult or an old person reading these lines. […] They die the same way they get lice or a skinned knee,” it feels more damning than comforting. mRb

0 Comments