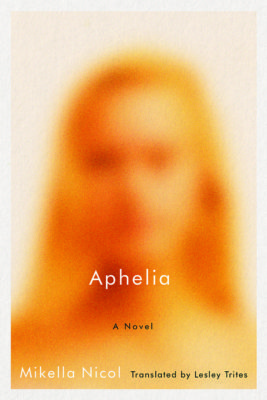

The cover of Aphelia features an out-of-focus photograph of a young woman. In the gauzy light, few of her features are visible beyond an outline of shoulder-length hair, dark eyes, and a smudge where her mouth should be. This haunting image neatly symbolizes the novel’s central character, whose name we never learn. The protagonist and narrator of Mikella Nicol’s second novel has become a stranger to herself. In the wake of a trauma that is uncovered over the course of the book, she is governed by impulses she does not always understand.

The novel opens during an early summer Montreal heatwave, and we find the protagonist in a strange holding pattern. She clings to routine, working the night shift at a call centre and meeting her best friend Louis every Friday at the bar where they have been drinking since high school. Her desire for the predictable also extends to her new boyfriend, Julien. A junior executive, he owns the condo where they live together, a pristine space that she finds lifeless and suffocating. Conflicting work schedules mean they rarely see each other, and Julien is able to ignore the signs of her increasing emotional distress.

Aphelia

Mikella Nicol

Translated by Lesley Trites

Esplanade Books

$18.95

paper

105pp

9781550655193

The novel consistently exposes the protagonist’s lost sense of self. She tries to see herself in the reflections of windows, blackened television screens, and mirrors, but never finds what she is looking for. Unable to recognize herself, she measures her value against others and frequently seeks validation from those around her. One patron of the bar who dresses like her becomes an obsession, a twin she is always trying to best. Her sense of her own selfhood comes mediated through encounters with others. She muses, “I would have much preferred to find another way to paint my own portrait than through my lovers, but I didn’t know how.”

She finds another reflection of herself in a young Montreal woman who goes missing without a trace. Following the story in the news consumes her. She often spends nights at the call centre on the phone with Mia discussing the details of the case. In the disappeared woman, the protagonist sees a vision of her own experiences of domestic abuse. Slowly, she begins to uncover the trauma that she has been medicating with alcohol and desperate romantic connections.

While reading Aphelia, I was sometimes reminded of the works of French Nobel laureate Patrick Modiano, whose slim novels often focus on a male protagonist’s search for a mysterious woman. In Nicol’s novel, the mysterious woman being pursued is the narrator herself, and she is also the pursuer.

Nicol’s writing is unflinching as she explores the rigours of twenty-first- century early adulthood. This short volume overflows with sex, alcohol, and alienation. The narrator’s sudden obsessions come to rule her entirely, only to lose their power as she moves on to the next fixation. It is a well-crafted portrayal of mid-twenties torment: bursts of intense passion interspersed with periods of depression and ennui on a backdrop of underemployment and horoscope blogs. However, Nicol’s vision is somewhat obscured by a clunky translation to English from the original French. Read on their own, individual strained sentences and instances of overly literal translation might be brushed off, but the experience of routinely being taken out of the story by slightly off language has a cumulative effect.

Aphelia doesn’t offer any tidy endings. By the novel’s close, most of the protagonist’s relationships are in tatters. Even so, when the feverish heatwave finally breaks, the narrator finds herself slowly coming into focus. mRb

0 Comments