Addie Tsai’s journey towards publishing Dear Twin, her first book, has been circuitous – with many side roads, some dead ends, and plenty of footnotes, not unlike the novel itself. Tsai, who has a PhD in dance, began her writing life as a poet, later moving into memoir before eventually excavating and reforming her autobiographical work to create Dear Twin, a complex and emotionally intelligent YA novel about mirror twins, family trauma, queer love, and self-discovery.

After some discussion over email, we met over FaceTime on the first day of the Lunar New Year – Addie in Houston, me in Montreal – to talk about literal and metaphorical twinning, queer Asian representation, reformulating YA literature, and the possibilities of healing in the aftermath of abusive family dynamics.

Dear Twin is the story of Poppy Uzumaki, a queer eighteen-year-old struggling in the confines of her domineering father’s house in suburban Houston. Her mother is barely present, and Poppy’s mirror twin Lola has gone missing, but nobody in the family is willing to do anything about it. Poppy is hellbent on getting Lola back – she begins writing her letters, one for each year of their shared and tumultuous lives, in hopes of convincing Lola to return, despite the fact that their relationship is anything but easy.

As the letters accumulate, the many contradictions of their twinned existence emerge. They have been both co-conspirators and adversaries since they were very young: “We weren’t the same, though no one could tell us apart. We were opposites. And that meant that everyone saw us as the same person, two bodies with joined names, one personality with two faces, a coil of sameness.”

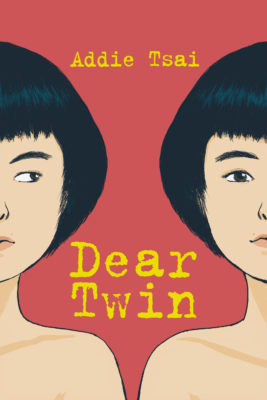

Dear Twin

Addie Tsai

Metonymy Press

$18.95

paper

280pp

9781999058807

There is a thread of parental neglect and abuse running through their story. While the twins’ mother flits in and out of their lives, parading them before her lovers, then disappearing, their father, Baba, is a surly and sometimes violent force whose attempts to exert control over Poppy and Lola result in pain and estrangement. Tsai is careful not to write Baba as a one-dimensional Evil Father, however.

“It would be a disservice to Poppy as a character, and to the complexity of family psychology and relationships in general, if we were to only see her familial relationships through a one-dimensional villainous lens,” she tells me. “Although Baba has caused much pain to his children or has inadvertently caused his children to be abused through his narcissistic willful obliviousness, he is also the reason that Poppy and her siblings have been able to have the lives that they do. Poppy is aware of this, and aware of her father’s limitations.”

Tsai is a mirror twin herself. “I wanted to write through my experience of being a mirror twin since I’ve not read any books that even address mirror twinning. But, also, I wanted to write twinning into the genre in a more complicated and complex way than I’d seen,” she says. “I wanted to show individual twin bodies – characters that are deeply impacted by their doubled life but also have their own separate lives to negotiate.”

From early on, even though Lola gets more attention than Poppy, she also tries to usurp Poppy’s interests, like writing. Tsai’s exploration of twinning and mirroring goes beyond that of actual twins, though. Dear Twin also looks at how relationships, perhaps especially queer ones, or queer Asian ones in this case, can involve mirroring, a twinning of sorts. Tsai puts it this way: “Navigating my own life and identity as a singular person in the world versus as a joined one – whether that’s as a twin, as a part of a couple, or even within intensive friendships – is always a unique struggle I will have, as I have never known a single day in the world where I was not also two.”

The process of reformulating her initial memoir into a work of YA fiction involved removing certain personal details and reflections and injecting a sense of fantasy and possibility into Poppy’s story. “I was trying to imagine a narrative for Poppy that was working out my own feelings about my past,” says Tsai. “What would it have been like if I could have had a queer relationship as a young person? What would it have been like to be a young person who does figure out how to break away from the family at a young age and go towards a new life?”

Dear Twin purposefully reinvents some of the more overdone elements of YA. “A YA trope that frustrates me is when so many girl-identified characters are so intensely misanthropic, sort of above the world,” Tsai explains. “I wanted Poppy, despite her traumatic upbringing, to be a character that still believed in the power of people to change and heal themselves, and to see the good in others.”

The central romantic relationship in Dear Twin is between two Asian girls – Poppy, our protagonist, and Juniper, her steadfast and loving girlfriend, who has to escape the influence of her own strict Korean mother. Tsai crafts a love story that goes against the typical YA romance tropes: there is no will-they-or-won’t-they, no unfulfilled gay longing, no white-saviour-swooping-in-to-save-the-lonely-narrator. Instead, Juniper is a grounding force in Poppy’s life, reliable and sweet and supportive. The only conflict arises when she leaves town on a college visit, and Poppy grapples with her fears of abandonment and betrayal. It’s clear that this fear is less about Juniper being untrustworthy, though, and more a projection of Poppy’s difficult twinship.

I ask Tsai how a book like this could have changed her life and outlook when she was a teen in the mid nineties, growing up in Clear Lake, a conservative suburb of Houston. “If I’d been able to read a story about being a twin or being mixed race, that would have been life-changing,” she says, without hesitation. “And then, if I’d read a story about a queer Asian girl…!” She shakes her head, and I nod, because I get it – it would have changed my young biracial Asian didn’t-know-I-was-queer-yet life as well. She goes on: “There’s a particular quality of coming out within a culture so focused on the good of the collective, where you’re not supposed to embarrass the family. There’s a particular social consequence that you’re placing on the people who have cared for you. It would have been a completely epiphanic moment, if I had known, not just that there were other queer Asian girls, but that a queer Asian person was out and could even write about it!”

When I imagine the future of YA literature, I hope for more books like Dear Twin – portrayals of the barbs and struggles of adolescence that don’t shy away from familial and relational trauma, yet are still imbued with generosity and compassion. Stories about young BIPOC lives, about reformulating love and family, about getting unstuck from never-ending cycles of hurt. Fortunately, Tsai is working on the sequel, in which we hear from the absent Lola. I can only predict that this companion text will be as nuanced and clear-eyed as Dear Twin. mRb

0 Comments