You don’t create one of the most widely read and discussed novels in all of literature by luck. George Orwell did it by writing a book that can be many things to many people, and whose ideas show no sign of growing outdated.

Frédérick Lavoie is a Quebec writer and journalist whose political engagement is deep-rooted: he once spent time in a Belarus prison for the offence of confronting corruption there. Hardly surprising, then, that he found his interest piqued by the republication in Cuba, after a decades-long absence, of Orwell’s 1984, and made three trips to the island to investigate. The result won the 2018 Governor General’s Literary Award for French-language Non-fiction in its first edition; now, no less timely for the lag, it gets its English translation.

Determined to find out exactly whose idea it was to reintroduce an explicitly anti-authoritarian book in the face of an admittedly fading authoritarian regime – on the condition that the new edition be furnished with an introduction in which the United States could be positioned as the bad actor – Lavoie makes three shoestring- budget trips to Cuba, and while his quest leads him mostly down a series of figurative dead-end streets, plenty is gleaned along the way.

The timing of Lavoie’s visits, from 2016 to mid- 2017, provided him a richness of incidents that he couldn’t have predicted. At first, Barack Obama, then nearing the end of his second presidential term, was taking concrete steps to lift the long-standing and increasingly gratuitous US-imposed blockade. His historic visit to the island was on the horizon; a mood of guarded optimism prevailed. Then Donald Trump was elected, and those Obama-led gains – and most people reading this book will agree that they were, indeed, gains – effectively evaporated overnight. Oh, and along the way Fidel Castro died.

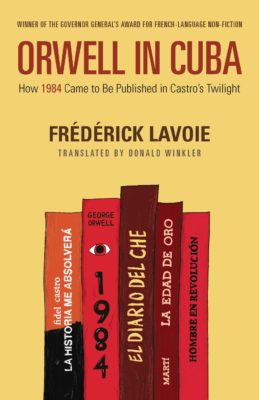

Orwell in Cuba

How 1984 Came to Be Published in Castro’s Twilight

Frédérick Lavoie

Translated by Donald Winkler

Talonbooks

$24.95

paper

304pp

9781772012453

The Orwell thread runs throughout. Time spent at a state-run archive reading in period newspapers of how Castro’s initial openness to the idea of democracy soon pivoted in the opposite direction inspires Lavoie to quote the timeless Orwell dictum that “one does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship.”

Elsewhere, noting the curious fact that Havana’s Museum of the Revolution ends its displays abruptly at the dawn of the country’s 1990s economic crisis, Lavoie reflects, “For a movement or an individual that does not acknowledge any errors, or so few, the only failures that can be talked about are those that have been overcome, or those that allow one to more definitively affirm one’s status as a victim.”

In the end, though, the greatest strength of Orwell in Cuba lies in the street-level view it affords of ordinary Cubans negotiating the absurdities of daily life as an entrenched regime is losing its grip. One such person, struggling to run a Havana restaurant in the face of severe supply challenges, is Mayrelis. “The embargo is internal first of all,” she tells Lavoie. “The country is not meeting its demands. […] Cubans are not used to getting up early, having responsibilities, producing. […] Our material condition is dependent on the udder of whatever foreign cow is prepared to help us out.”

Orwell would have understood. mRb

0 Comments