Berenice Einberg, the adolescent protagonist of Réjean Ducharme’s novel, is neither conventional nor sentimental. Yet even this iconoclastic and borderline feral character is moved by the transport that reading provides. As she muses, “A book is a world, a whole world, a world with its own beginning and end. Each page of a book is a town. Each line is a street. Each world is a home.”

The history of Ducharme’s first novel asks the question of what happens when we lose the map to that world. The French original, L’avalée des avalés, was published in 1966 and launched a career that would see him produce novels, plays, screenplays, and musical collaborations while also remaining famously reclusive. Barbara Bray produced an English-language edition in 1968, which received little recognition from readers and critics. Since the well-reputed Parisian publishing house Gallimard had been responsible for the French-language edition, this first English translation was published in the UK and marketed primarily to a British audience, which might explain its reception. Bray’s edition has been out of print for decades. This new edition, translated by Madeleine Stratford, offers English readers access to a work that manages to be both intimately familiar and utterly strange. Reading Stratford’s rendition is an immersive experience: the novel is indeed its own world, where language and plot operate with their own logic. Joyce and Salinger offer a starting point for evoking the stream-of-consciousness narration, lyrical play of language, and charisma of a character who plays by her own rules, no matter the cost.

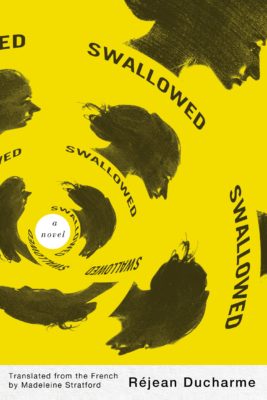

Swallowed

Réjean Ducharme

Translated by Madeleine Stratford

Esplanade Books

$22.95

paper

260pp

9781550655537

The pathos of the novel rests on the tension between Berenice’s need for self-actualization and her need for a sense of belonging. While she lashes out at anyone and anything that might try to contain or constrain her, she also sees herself as enmeshed in history. The text is littered with allusions, historical references, and punning wordplay that only occasionally conforms to the standard we call accuracy – as Stratford wryly notes, “Berenice does not care much for the truth.” The novel isn’t an easy read, and it probably isn’t for everyone. And yet, more so than anything I’ve read in a long time, it seems futile to wish for this text to be in any way different from how it appears on the page. Berenice explains with her trademark utter lack of self-consciousness, “To be someone is to have a destiny. Having a destiny is like having only one destination. When you only have Budapest, you have one alternative: either you go to Budapest or you don’t. You can’t go to Belgrade.” Either you read Ducharme prepared to inhabit the world as he creates it, to be swallowed up by it, and to surrender to it, or you miss the encounter with the force of the story altogether. I recommend the former. mRb

Thank you for this. I had to read the original French as mandatory reading in courses. Maybe time to go reread.

Lovely piece Danielle!