Kama La Mackerel’s debut poetry collection, ZOM-FAM, is kaleidoscopic – literally, it is beautiful in its form and scope. As a way of looking, the kaleidoscope lets us view and appreciate La Mackerel’s moving, imaginative poetry through multiple frameworks. ZOM-FAM may be described as a series of eight long lyric poems; a queer trans epic; a text of gratitude and celebration; and, as La Mackerel said, they have written “an entire piece about my own journey in terms of stepping into my femmeness […] stepping into my trans-femininity, finding a language and ancestral language within which to articulate my body and my gender.” The same way a life, place, or family can’t be easily summarized, these phrases just begin to describe ZOM-FAM and how it achieves its complex textures. In ZOM-FAM, La Mackerel is “rendering the language already hybrid,” they told me, and hybridity captures the way the book reclaims/recreates languages and performs dynamically on the page.

During our conversation one morning, La Mackerel also offered Audre Lorde’s coinage for her 1982 book ZAMI, saying ZOM-FAM follows in the tradition of biomythography, a hybrid form combining biography, mythology, and history – a form La Mackerel makes look effortless. The speaker is born on a “zourne mofinn” into a landscape that is vast, yet particular, where “heat rose // from the ocean,” “geckos gathered on top of banana trees” and fishermen were “drinking arak under filao trees.” These lines are examples of many details subtly pointing to the political history of Mauritius, while also grounding the reader in place. The words zourne mofinn repeat, and roughly translate to “day” and “jinx” from Kreol, a language developed under the French colonizers’ enslavement of people taken from their homes and whose native languages include Malagasy, Wolof, and some East African Bantu languages. Notably, European colonizers also brought the filao trees to the island in the eighteenth century.

Images of place go on to underscore the themes in “your body is the ocean.” La Mackerel explained, “I really wanted to explore writing the queer body in relationship to the island” in addition to “the ways in which my parents, my family, my grandparents experienced colonial history.” The colonization of Mauritius – a place “where the smell of collective trauma / hangs like dried octopus under the sun” and where “dreams hummed / like the engine / of a sugarcane factory” – reverberates throughout the book, but it does not precede where ZOM-FAM begins.

In the first poem, “the invocation,” a song of gratitude, the speaker opens “i invoke our mothers, our grandmothers & our femme ancestries […].” This opening calls ancestors, spirits, goddesses. It acknowledges suffering and resilience, story and silence. La Mackerel said this practice of gratitude keeps close some central questions of their work. They ask, “What makes our lives possible? What allows us to do the work that we’re doing to live and love within the context that we’re in?” In a time when we face a tangle of climate disasters, white supremacist violence, and a pandemic – but also, when we have joy, community, and love – it’s difficult not to feel the gravity of La Mackerel’s questions pulling us to pause and reflect.

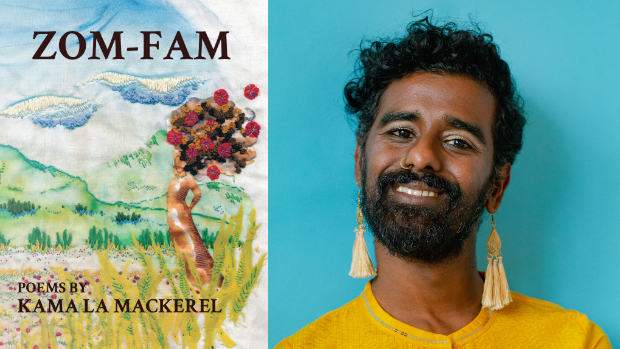

ZOM-FAM

Kama La Mackerel

Metonymy Press

$16.00

paper

104pp

9781999058845

Another way in which La Mackerel shows their skill is through their treatment of story. The speaker examines the ways stories connect us, but also how they can serve as social control. The fourth poem, “existence as gender survivance” begins, “when you grow up a queer femme child on a plantation island / there is a story scripted for your body.” Story, anaphora, and form issue a kind of limit around what the speaker is supposed to be, but also how they find a way:

to witness.……….femme intimacies

……………………….storytelling

……………………….gossip

……………………….sisterhood

……………………….support

……………………….softness

……………………….pointed & sharp

……………………….like a cooking blade

This turn on softness shows how La Mackerel holds space for complexity, a gesture that extends to the ways in which languages weave into ZOM-FAM. In “twenty years of brick,” La Mackerel explained “the building of the house becomes the only language the father can use” and before that the father “chanted prayers / in a language he could not even understand.” This continues with the story of conversations in which the speaker talks to their mother about being trans:

she whispers into the soles of my feet

……….that she vaguely remembers an old relative

who lived close-by… when she was a child…

………..who was… who was…“of my kind…”

What is said and silenced creates an atmosphere where the speaker, as La Mackerel put it, can honour multiple ways of being and speaking, and explore an epistemology not steered by Western frameworks or narratives. Although ZOM-FAM is written in an im- perial language, the title is a refusal to be wholly un- derstood in English terms. For the speaker, zom-fam is a connection to lineages, “spirits / lost in the kala pani,” and lost languages. The word and its story also highlight dynamics between generations and the erasure that can happen when imperial languages are prioritized. ZOM-FAM is reclamation and offering of languages of love. La Mackerel added, “zom-fam, as a way of existing outside of the gender binary, for me, is a decolonial way of being in the world.”

The languages of love radiate across the whole book and feel especially warm when the speaker answers their mother’s ellipses with a “dream of this old relative who was… ‘of my kind…,’” whom they name Kumkum.

Kumkum eats rice, dal & pickles during the week

& on weekends, she treats herself to some dried, salted fish

cooked with onions, fresh thyme & tomatoes

………….enn bon ti rougay pwason

………….sale bien morisien

The everydayness Kumkum lives is a way of speaking the languages of love, which carry through La Mackerel’s beautiful book. There is still more to be said about the multifaceted music and skill ZOM-FAM offers, but I end here with Kumkum living her life:

when it gets hot in the capital city

Kumkum takes out a white embroidered handkerchief from her purse

& wipes the pearls of sweat from her forehead. mRb

0 Comments