Popular culture has a kind of romantic notion of Yiddish as an outlandish, playful, mouthfeely language where every word is an onomatopoeia; it’s the language that gave us chutzpah, shlemiel, dreck, words whose meaning you can taste as you say them. It’s where we turn for grotesque insult, gut-level contempt, grievous offence. We might forget, then, that for generations of Eastern European Jews, Yiddish was the language of daily life – it expressed tragedy, boredom, affection, and tenderness, alongside all that great trash talk.

Yiddish is also haunted by loss – as those communities of Eastern European Jews were wiped out in the Holocaust, so was the language diminished. But pockets of diasporic Yiddish-speakers still thrive, and small, dedicated groups are committed to preserving and disseminating the best work of some of its lesser-known writers through translation.

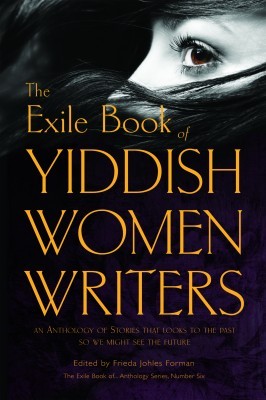

The Exile Book of Yiddish Women Writers

Edited by Frieda Johles Forman

Exile Editions

$19.95

paper

306pp

978-1-55096-311-3

The stories themselves span decades and nations, from the Eastern European shtetl to a socialist commune in the Crimea, from the recently liberated Lodz Ghetto to a cottage in the Laurentians. They shed light on Jewish women’s daily and lifelong struggles in the last century. Several focus on a longing for education and experience denied because of gender, while many more deal with the efforts of Holocaust survivors to continue their lives. They capture a rich cross-section of experiences, and they do so in the rhythms and the cadences of a marginal language, a language that carries with it the traditions and experiences of a world that’s not exactly lost, but sometimes hard to see.

Anna Leventhal: Why do you think women’s voices have largely been left out of Yiddish writing in translation?

Frieda Johles Forman: Translation is a political act – in order to get translated you have to have some power. And women writing in Yiddish were not in that category. We’re living in a world where women don’t always get a fair deal – that part I don’t need to elaborate. Now, when it came to Yiddish women writers, it’s particularly hard to understand, because in the Yiddish-speaking world, women actually had a good position. There weren’t as many as men, but they were not unknown. But in the last half of the twentieth century, if you asked anyone in the English-speaking world to name a Yiddish woman writer, they would scratch their heads. So something happened in the process between the original language and the translation. The visa or the ticket you needed to move from one language to another didn’t exist until the women’s movement came and issued it.

AL: As an editor, what guided your selection process? What were you looking for in the stories you chose?

FJF:We wanted material that really highlighted women’s lives, that showed women in a light different from the one in which male writers had shown them before. The other thing that’s unique to this volume is that we wanted a lot of Canadians. That was really one of our goals – because if we weren’t looking for Canadians, no one would be.

One interesting thing is that the stories we translated didn’t have sentimentalized views of the shtetl. They reveal it for what it was – it had a lot of warmth, and a lot of passion for learning, but it also had limitations. And that’s one of the themes we hope the book will convey – the yearning for a wider world, beyond the restriction of narrow shtetl life. As an editor I’m very drawn to that expression. To me it’s one of the aspects of the human condition that I find the most engaging, the most compelling. And here we find it in great quantity. In some cases it’s so simple, like the Ida Maza story, where there’s a little girl who says she wants to learn, and her brother says, “You can’t, you’re a girl.” You know, when Isaac Bashevis Singer wrote Yentl, he was writing what Yiddish women had been writing for decades.

AL: In one of the later pieces, an essay by translator Goldie Morgentaler, she mentions this conversation she has with her mother Chava Rosenfarb, a well-known Yiddish writer, where Morgentaler says, “You can’t say this, it’s too mushy, too sentimental, too many adjectives,” and Rosenfarb responds “English is such a cold language!” How would you characterize Yiddish as compared with English? And what were some of the challenges in translating it?

FJF: Are you familiar with the term “Yinglish?” There are a number of writers that were very popular earlier in the century, and were reclaimed by the women’s movement in the 1980s and 1990s, Anzia Yezierska, for example. These were immigrant women who wrote in English, but with great Yiddish flow to it. For example, in Yezierska’s work she’ll use expressions like “It became dark in front of my eyes.” Now that’s not real English – but it’s Yiddish. When you read her Yinglish, you can translate it back to Yiddish, because you know that’s what she’s thinking.

Now, we didn’t want to continue in that frame, although it played a very significant role in its day. We wanted something that could be read in English with some pleasure. On the other hand, we didn’t want it to sound like Alice Munro or Margaret Atwood. We wanted it to have something of the choppiness that some Yiddish writing has. Yiddish writing isn’t always that fluid, it doesn’t just melt. It goes along and it stops and then it starts, so it has a kind of energy that’s different from English. I’ve read Yiddish translations that sound like they were written by an American writer, and that’s lovely reading, but it doesn’t give you the flavour of Yiddish.

AL: There are some great writers in English where you can really feel the influence of Yiddish. I’m thinking of Grace Paley and Saul Bellow, for instance.

FJF: Especially Grace Paley. Her storytelling has a very Yiddish quality to it. I love her work, and I love Saul Bellow. It’s interesting that you mention that these writers that we all revere still have something left of another culture. When you’re translating Yiddish you’re really translating another culture as well. Yiddish is unique in the sense that it’s steeped in Jewish culture, so it might be difficult for non-Jews to understand the references. You can’t assume that if someone says shemona esray or one of the prayers, that people will know what it is. And why should they? So we end up with glossaries. It’s not ideal, but what is?

AL: At the same time, there’s something to be said for creating a world and letting people enter it at their own pace, not worrying if they understand every word.

FJF: Exactly. Literature wants to give us another world that we can enter – that’s what good literature is. And I think this book, taken as a whole, opens up a number of worlds. It opens up, for instance, for those of us of Ashkenazi background, the world of our grandmothers, which we didn’t know before. Nobody really knew their daily lives. And now we do. mRb

0 Comments