I t’s hard to place what Patrice Martin’s agenda is with Kafka’s Hat. The back cover describes his first novel as a “ticklish tip of the hat” to the writing of Franz Kafka

and a “labyrinth of intertextual references.” Whether or not so-called hat-tipping is justification enough for a novel, if Martin aims to evoke the work of his idol, he’s somewhat missed the mark. Consider: would Kafka ever introduce his docile protagonist to a spirited young lady who would steal his heart, teach him to privilege his own judgment, and get him – egads! – laughing?

Probably not, though according to his bio Martin has been “bumping into the spirit of Kafka for most of his adult life” and spent years working in government, likely from whence comes his insistence that mindless bureaucracy is a horrible thing. But Kafka was arguably less concerned with the literal experience of bureaucracy as with the terrifying spectre of immutable authority and the painful existential conundrum we find ourselves waking to every morning. Martin’s take on his idol has made him rather smaller than that, and his inspirations don’t stop short at Kafka; Kafka’s Hat is a dense and cerebral work that repeatedly alludes to Borges, Auster, and Calvino as well.

Stylistically, Kafka’s Hat lacks those magical details that bring a novel alive; it has the bones of a story, albeit with a touch of osteoporosis. The reader meets the hapless bureaucrat P., a man who “wants to preserve the world in which he lives” and “has always defended the established order.” P. is given the task of picking up Kafka’s hat for his boss Mr. Hatfield, who purchased it at an auction. P. so wants to impress Mr. Hatfield, but a series of zany events ensues that compromises his ability to recuperate said hat. The reader follows P. as he discovers that bureaucracy is full of shit and too often negates our better human qualities.

In section two, Martin introduces a writer named Max who has written a manuscript about a man going to pick up Kafka’s hat for his boss. Max drives to New York in a desperate bid to track down Paul Auster and maybe even convince him to translate his manuscript into English. (Paul Auster most definitely did not translate this book. A woman by the name of Chantal Bilodeau did.)

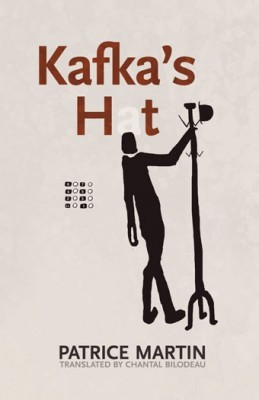

Kafka’s Hat

Patrice Martin

Translated by Chantal Bilodeau

Talon Books

$12.95

paper

144pp

9780889227439

The difference between a new writer like Martin and a classic writer like Kafka is that Kafka’s style produces a notable effect on the reader. There is a disturbing quality to his writing, a sense of the writer’s soul laid bare between the words. It’s got that punch-in-the-gut feeling that is conspicuously missing in Kafka’s Hat. The main problem with Martin’s first go at a novel is that it is mostly intellectual play and self-conscious recycling, leaving the reader cold and not particularly affected. What happens to the lost soul cast into the shuffle of inefficiency and bureaucratic bloat? What can the absurdity of bureaucracy tell us about humanity? What does a self- referential novel accomplish, aside from tired postmodern cleverness?

To be fair, reading enough first novels has lowered my expectations sufficiently that I will say this was a pleasant read, and I occasionally looked forward to picking it up again. With some work, Martin could use his inspirations to produce much stronger writing. The crucial question is how does his own approach fit into all this wanton hat-tipping? One can only hope his second shot at a novel reflects a little more of his own identity as a writer and a little less of his very laudable influences. mRb

0 Comments