“I think Babies “R” Us is one of the saddest places there is – everyone looking to buy something that will make a very traumatic and life changing experience into something more manageable.” Like her main characters, Jennifer Quist does not hesitate to express firmly held, intelligent opinions. That’s her talking about birth. You should hear what she has to say about death.

Love Letters of the Angels of Death is very aptly titled. Don’t be fooled by the reference to angels; this is no New Age fluffball. The book opens with decomposing human remains, and includes a corpse lowered into a grave filled with water and another buried in concrete. (It’s probably not what you think, but Quist lets you think it just long enough to let the idea take form in your mind.) Not to mention the quirks of the living, like the elderly woman who sleeps on a table saw. But the characters’ experiences with death make them “better able to empathize with each other and live together.” In spite of the abundance of funerals (there are a few weddings too), this book is that rarest of literary portraits: the story of a genuinely happy marriage.

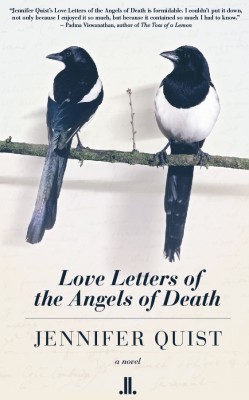

Love Letters of the Angels of Death

Jennifer Quist

Linda Leith Publishing

$16.95

paper

222pp

978-1-927535-15-8

Literature offers few images of really good, healthy marriages. Tolstoy’s famous remark about all happy families being the same implies that they’re boring, but Quist’s lovers, Carrie and her husband Brigs, are engaging from beginning to end. They navigate the perilous waters of everyday life with humour, tenacity, and integrity. Clearly, Quist understands how happy marriages work. Not that the book is strictly autobiographical. “I let the book family off easily,” she says. “HA!”

The book is set mostly in Alberta – there is a vivid Fort McMurray – with occasional references to Edmonton landmarks and the “bald prairie” around Calgary. But the book also travels to several Maritime settings. For Quist, Love Letters is not particularly an Alberta story, but is naturally pan-Canadian, since it follows the route taken by many Canadians to travel between regions.

Quist keeps us interested as her loving couple copes with various deaths and smaller disasters thanks to her sensitive observations and deft turns of phrase. A pile of kids’ winter clothes “looks like the boys came home from school and then just exploded inside the front door.” A charred wooden wall “looked like it was cobbled together out of tiny coal tiles.”

The second-person narration, with Brigs telling their story to his wife, is a risky choice, but it almost always works. There are artificial-feeling moments when Brigs recounts events and emotions he could not have been privy to, but that’s part of the point: in this marriage they see and feel the world through each other. Although, at the very end, this is carried to an extreme that is more technically consistent than emotionally effective, it works well enough. It’s one of the details that Quist drew from life. After her husband lost a parent, she managed her and her husband’s grief “by tuning into his feelings and his perspective. It was a survival measure,” she says. In Love Letters, it is at the core of Carrie and Brigs’s practice of loving marriage. This radical empathy is one of the book’s joys.

“During those few days,” Quist explains, “nothing mattered to me but his experience.” Putting her mind to her husband’s experience seems to have fitted Quist beautifully to write from a man’s perspective. She has also benefitted from life with five sons. “I’m outnumbered six to one by men. I’m soaked in the male psyche.”

Brigs and Carrie have four small sons, but there is a strange absence of toddler life. Carrie never seems to have mashed banana on her T-shirt or crusty egg yolk in her hair; there is no sense of the constant parental struggle to get enough sleep or eat a blissfully uninterrupted meal. The kids are constantly being left behind with someone’s aunt while Brigs and Carrie run off to deal with another family crisis. This is not so much a story of parenthood as it is the biography of a marriage, complete with its prehistory in childhoods and family histories. Death reveals family dynamics that other writers might have shown through scenes of domestic life. Quist is interested in death because of how it affects us: “Western death rites have become a product – a prepaid package deal. My personal theory is that it’s because the social responsibility for dispatching the dead became a mostly male responsibility and many of them would rather just write a cheque and sit it out. The death industry is over-processed and just about everything about it seems targeted at making all contact with the dead body extremely controlled, absolutely voluntary, and overseen by specialists from outside the family unit … I don’t think this is good for people.”

The opening scene of Love Letters is a graphic (but not disgusting) description of Carrie and Brigs coping with the deliquescing corpse of his mother. It reads a bit like a murder mystery starring a forensic expert – but Quist’s point is that death is not to be left to experts. “I think it makes them better able to empathize with each other and live together,” she explains. Like birth, death has been too professionalized, too abstracted, leaving us at a loss when faced with these very intimate aspects of life. Searching the shelves of Babies “R” Us, “we’re trying to find a way to write a cheque and then show up as honoured guests at the big event, the way we do with death. But … birth – or at least the postpartum aspects of it – is still something women have to pass through themselves inside their own bodies.”

The love letters that Carrie and Brigs, the angels of death, accumulate for the reader in the gradually revealed story of their marriage are not sentimental in the least. Nor is their happiness due to a trouble-free life. On the contrary, it comes from the closeness they create by seeing each other through the whole shebang. The good times, of which there are plenty. The moments when they struggle to work out how to live right. And the painful times, all the mess and weirdness and occasional shocks of being part of a scattered family with its full complement of foibles and failings. Brigs and Carrie never stop “writing” the love letters that make up both life and death.

“It’s hard but it’s good for us,” says Quist, “and for the people who need to step up and care for us.” mRb

0 Comments