When we talk on the phone, I ask Julie Doucet about the concept of maximalism, one of my favourite words and driving forces that I feel accurately describes both the style and attitude of her work, but Doucet doesn’t relate to it. “Maximalism?” she asks. “No, no, no.” Doucet tells me that a lot of her work and composition on the page (especially her printing work) contains a sparseness. A single figure in the centre, with space around it.

Doucet’s style is characterized by fine pen work, with hand-drawn, high-contrast squiggly lines that fill her panels so suggestively that the more you look, the more you see. Her content is self-referential, and includes dreams, personal fears and fantasies, day-to-day life, personal relationships, worries, as well as all-too-familiar conflicts about the life and identity of an artist. And it’s paved a wide road for creators – especially those who aren’t cis men – to walk down behind her.

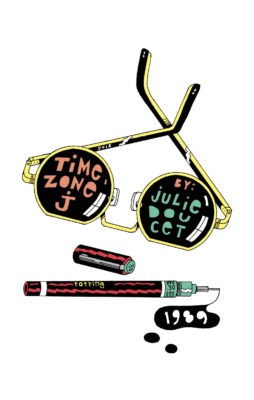

The world-building in her work is so very Montreal. The objects packed into her small dirty apartment in her early work My Most Secret Desire (1995) talk to her, and frequently insult her. The pages in her most recent work, Time Zone J, are completely filled with faces; her own (many times on one page, at different ages and angles), faces of celebrities, birds, and squishy bonhommes.

Time Zone J Drawn and Quarterly

Julie Doucet

$34.95

paper

9781770464988

Despite Doucet’s frustration with sexism in the comics scene, she was prolific: her serial comic, Dirty Plotte, originally published from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, was serialized in 2018. Her work has inspired so many personal journal comics and zines by other Montreal creators, such as the Nailbiter series by St. Emilie Skillshare, the work of Mirion Malle, the Trauma Castle series by Stela Starchild. I credit Doucet with influencing my serial comic zine, Squirrel Grrl, as well.

I am about a decade younger than Julie Doucet. When I arrived in Montreal in 2000, the city was layered with bright, dense, screen-printed posters, and contained a robust fanzine and comic culture. Think of the yearly Expozine, the Distroboto machines distributing zines and small artworks for $2 apiece, the many shops that featured zine racks near the cash in both Franco and Anglo scenes. The comic scene welcomed women artists in its inclusion of personal themes in various messy, expressive, photocopiable styles. Feminist activism often centred around lesbianism and reproductive and menstrual health. There were plenty of places to buy reuseable menstrual products, like Elle Corazon. But the scene had its flaws, which are easier to see now. The feminist art scene at this time was dominated by white women, and was for the most part transphobic, especially towards transwomen.

It was a scene I felt surrounded and embraced by. But over the phone, Doucet reports that the comics scene in which she found herself in the early 1990s was a restrictive, unwelcoming boys’ club – one where personal comics with imprecise lines were not considered comics. “They thought it was an art book, or a sketch book. They said it was ‘interesting,’ which wasn’t a rejection, but they didn’t consider it comics,” she tells me. This story is included in her book 365 Days (2007), and reveals her publisher’s reaction to her work, and her reaction to his reaction. Her comics relay her stress, sadness, and plans to move away from Montreal.

It was a scene I felt surrounded and embraced by. But over the phone, Doucet reports that the comics scene in which she found herself in the early 1990s was a restrictive, unwelcoming boys’ club – one where personal comics with imprecise lines were not considered comics. “They thought it was an art book, or a sketch book. They said it was ‘interesting,’ which wasn’t a rejection, but they didn’t consider it comics,” she tells me. This story is included in her book 365 Days (2007), and reveals her publisher’s reaction to her work, and her reaction to his reaction. Her comics relay her stress, sadness, and plans to move away from Montreal.

In contrast to the comics scene in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Doucet tells me, the printmaking scene was more inclusive. Graff (a member-driven print atelier that still exists today) welcomed Doucet and others in at that time, and their work went on to fill the streets, surrounding Montrealers for at least two decades. I thank Doucet for making work that made space for other women artists, zine makers, and comics, and she quietly replies, “I guess it was good I made those comics. But I still hold a lot of resentment.”

Time Zone J was originally drawn as a continuous image in an accordion book format, over five books, and designed to be read from bottom to top. The book tells a riveting story, and reminds me of an Elena Ferrante novel. There is beautiful tension in small moments, an overwhelming love story is taking place. There are pieces of the story that a keen reader may find revisited from My Most Secret Desire. Time Zone J is like beautiful wallpaper with a story packaged up in a book format. You’ll want your face to be really close to the pages as you read it.

Doucet tells me that as a young child she drew scenes of crowds similarly to the pages in Time Zone, J, “but with no objects or animals, only people.” While so much is being shown, so much is also being hidden. Doucet says she knew what story she wanted to tell, but the pages themselves were improvised: “I had enough planning from the rigid style of comics. It was too frustrating.” I was shocked that the papers were not planned out: the line work is pristine. She laughs when I say so. “Well, I used a lot of white-out!” she replies.

Doucet tells me that as a young child she drew scenes of crowds similarly to the pages in Time Zone, J, “but with no objects or animals, only people.” While so much is being shown, so much is also being hidden. Doucet says she knew what story she wanted to tell, but the pages themselves were improvised: “I had enough planning from the rigid style of comics. It was too frustrating.” I was shocked that the papers were not planned out: the line work is pristine. She laughs when I say so. “Well, I used a lot of white-out!” she replies.

Sometimes the images feel like hand-drawn memories of magazine pages. To me, repetition seems central to this mode of storytelling, but when I bring up the word “repetition,” Doucet disagrees, although she acknowledges that “the book is about reminiscing.” For Doucet, Time Zone J is a freer project than comics-making. The pages are filled to the very edges, with no panels or any other kinds of divisions. In fact, the pages are one big image, overflowing and continuing beyond the page.

Whenever you open a project by Julie Doucet, no matter when it was made, it has a life of its own that continues to bring insight. Doucet’s work from decades past, and all the work she will make into the future, will continue to have a lasting influence on artists in Montreal and beyond.

Doucet talks freely in our conversation about her frustrations with the gatekeeping boys’ club that dominated the comic scene, both in Montreal and really everywhere, but she is quick to point out that she has dear male friends in the scene to this day, and that it would be unfair to paint it all with the same brush. “But sometimes,” she tells me, “I just want to SCREAM!” mRb

0 Comments