Those who must face horrific, uncontrollable life events are forced into navigating a place in the human soul that teeters dangerously on the border of irreversible madness. This permeable frontier has never been so well described as it is in Andrée A. Michaud’s novel Trembling River. I completely understand why psychological thrillers are not everyone’s cup of tea. To engage with this type of work, the reader must be willing to delve into their own psyche, to actually connect (at least to a certain extent) with what is taking place. In the first couple dozen pages or so of the novel, I had to work on not putting it down.

One of the two narratives involved a father dealing with the disappearance of his daughter. No parent can read about missing children without turning off a switch in their brain to prevent their own thoughts from spiralling, and here I was reading a novel which had me circling this zone uncomfortably. The other narrative is about a woman who cannot get past the disappearance of her childhood friend back when she was eight years old. What fascinated me (and most likely the reason why I kept on reading) was the way Michaud describes the psychological ravages of this untenable situation on those who were going through it. Her deep dive into the absurdity of losing someone, and never being able to mourn their disappearance properly, feels true.

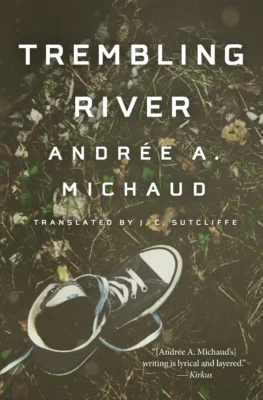

Trembling River

Andrée A. Michaud

Translated by JC Sutcliffe

House of Anansi Press

$22.99

paper

416pp

9781487005894

What finally ends up bringing these two characters together is the village of Rivière-aux-Trembles, and the disappearance of another child. This is the village where Michael disappeared back in 1979, and where Marnie returned to in 2009 after her father’s death. It is also where Bill bought a house on a whim that very same year, in an attempt to get past the trauma of Billie’s disappearance. The reader finally gets a better look at the infamous forest that claimed Michael in 1979. Its edge runs along the back of Bill’s recently bought house, which also happens to be close to Marnie’s childhood home.

This is not just a regular forest. Michaud skillfully turns it into a full-fledged protagonist, one that will divulge certain of its secrets through the words of Phil, Marnie’s father’s best friend, and through the eyes of an owl. A space that mirrors the far reaches of Marnie’s and Bill’s tortured souls, the forest is also a physical place where both find refuge but also confront fears simultaneously, and where things come together, where the story “gels” and both characters are able to find some sort of peace.

A huge hand of applause must be given to JC Sutcliffe for having spectacularly maintained this eerie space in translation. When the inner dialogue of characters meandering down the frightening path to madness makes up most of the pages in a novel, it often becomes difficult to separate what is real from what isn’t. This challenge is all the more heightened when translating. The writing here is masterful.mRb

0 Comments