Deep into Marie Héléne Poitras’ new novel, Sing, Nightingale, a shift takes place. What by all appearances sets out to be a conventional, dark fable unfolding on a feudal estate transmogrifies into something else completely. Things are not as they appear. The damsels in this book are not in distress; they’re causing it. And, as it turns out, for good reason. There are two worlds on the Malmaison estate: the one seen in the light of day, and the one shrouded in pain and secrecy – the realm of the desideratas. Poitras brings this unseen world to the surface, exposing the horrible truths the Berthoumieux family has hidden for generations.

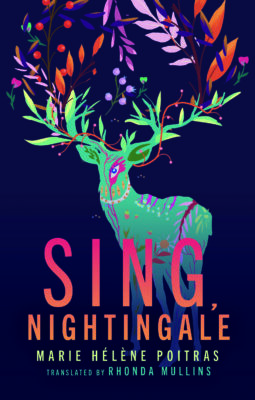

Sing, Nightingale Coach House Books

Marie-Hélène Poitras

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

$22.95

paper

176pp

9781552454480

It soon becomes clear that Aliénor is a force of disruption and chaos. She is angry. Very angry. And does not try to hide it. Untangling the source of this rage imparts a deepening sense of mystery, and as terrible secrets come to the surface, generation upon generation, the reader begins to understand her drive to “annihilate their name,” “break their line,” and “leave their manor in ruins.”

Rhonda Mullins has done a masterful job on what her translator’s note calls the “archaic and obscure French terms” of the original French novel, La désidérata. Poitras’ prose is rich, steeped in the senses, suffused with painting, perfume, and culinary decadence. Traditional French folk songs (with English translation) enliven the text throughout, and the story-within-a-story of Pimparela grounds the novel in fable, while bringing the brutal nature of Noirax society more into focus. The novel is meta-aware of itself as a piece of human creation, referencing “curtains,” and “intermission,” and late in the book, when Aliénor says: “I’m tired of the twisting stories and shadowy chapters. I want to see what’s in the blind spot,” she is very much speaking for the reader.

The world that Poitras weaves in Sing, Nightingale sits outside of reality. At times it’s a puzzling blend of the archaic and the contemporary, where boar hunting, witchcraft, and minstrels mix with sulfite-free wines, single-use plastic bags, and soy milk. Place names are familiar yet alien: Saud, Ouestan, Finistax. Behaviour that would be unthinkable, like drinking milk from an acquaintance’s breast, or making out with a market vendor for a bag of chestnuts, comes across as everyday sociability. Yet regardless of the fact that people can have green skin, purple hair, and blue irises, the patriarchal oppression at play is very familiar. In the ancient struggle between blood and milk, the cursed desideratas will be silenced no more. Their counter-narrative must be written in the body for future generations. And although Poitras delves deeply into what one might call gothic body horror, in the end Sing, Nightingale is a fairytale. The forces of care and nourishment have had their revolution, and taken their rightful place at the head of the table.mRb

0 Comments