Marie-Célie Agnant’s 2015 novel Femmes au temps des carnassiers, recently translated as A Knife in the Sky, is bookended by the rise of François Duvalier in 1957, and the overthrow of his son Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1986. During this period, Haiti suffered unbearable violence.

From the first page of the novel, the reader is plummeted into a world framed by continual threat. Mika, a journalist modelled on the Haitian journalist Yvonne Hakim-Rimpel, waits in a deep state of fear. Hiding in her apartment, but refusing to be silenced, she continues to critique the emerging regime of violence under Papa Doc and his paramilitary army, colloquially known as the Tonton Macoute, while trying to take some comfort in daily domestic routines and visits from the women in her family.

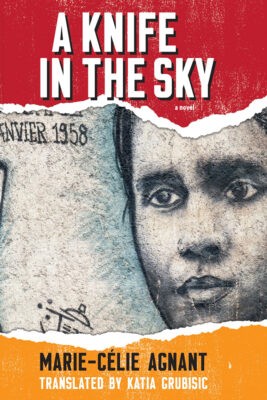

A Knife in the Sky Inanna Publications

Marie-Célie Agnant

Translated by Katia Grubisic

$22.95

paper

174pp

9781771339186

The second half of the book follows the story of Mika’s granddaughter, Junon, who, though born in Spain, inherits the traumatic memories of Haiti through a troubled relationship with her mother Soledad. Much of this section of the book follows Junon’s process of coming to terms with a past that occurred before her own birth, most notably an incident of torture that forever shook the lives of her mother and grandmother, and which echoes the real story of Hakim-Rimpel. The rest of the book explores the deep consequences this horrific event will have in both their lives.

Though one of its most remarkable accomplishments is to capture the fever dream of violence that the people of Haiti lived through during this period, the novel has the added attribute of familiarizing the reader with a history whose details are so often relegated to a footnote. Names such as Lafontant and Péralte are evoked – the former Roger Lafontant, a leader of the Tonton Macoute; the latter Charlemagne Péralte, a nationalist leader who was killed for resisting the US military occupation of Haiti. Though the book delves more into emotional resonance than historical analysis, it certainly participates in that great tradition of Haitian literature (Edwidge Danticat and Marie Vieux-Chauvet come to mind), whereby history must live in fiction because it is so little accounted for elsewhere. This is, of course, familiar territory for Agnant, whose Le livre d’Emma and Un alligator nommé Rosa evoke the trauma suffered by the women of Haiti in particular.

In Agnant’s dedication, to the memory of Yvonne Hakim-Rimpel, she writes that “a story silenced is a story slaughtered.” This theme of silence is at the heart of the book, and the choices that people make on whether to uphold that silence for their own dignity, or to speak in the face of unspeakable violence, are choices that frame their sense of self. At the beginning, Mika, unable to write of the events around her, quickly jots down instead: “They have succeeded for one whole day in depriving me of speech.” Later, after the attack, when she has chosen to forgo her journalistic speech (among other forms of communication), it will be her granddaughter Junon who asks the perennial question of all those born under the shadow of violence: “How could I speak the unspeakable?” And it is in returning to Haiti, to witness the final days of the Duvalier regime, that she seeks her answer. As always, Agnant’s gift for bringing readers deep within the emotional tension of a moment creates a stirring novel. This translation is clearly the product of a mutual poetic understanding between the author and translator, as Katia Grubisic renders all the fierceness and hope, laughter and despair, into language that goes straight to the heart of the reader.mRb

0 Comments